With the democratization of genealogy research in the digital age, once nameless ancestors suddenly add color and shade to our family portraits. For the first time, this access is allowing us to reimagine our ancestral past beyond the collective experiences of shared traditions, institutions, and an epochal story of national survival. And while the jury may still be out on whether retracing our family trees is an exciting hobby at least or a life-changing personal journey at best, studies over the past decade suggest that knowing our roots has a profound impact on how we see ourselves and how we live our lives.

Psycho-Social Benefits of Family Stories

“Knowing family history provides a sense of strength and resilience. Even knowing difficult stories can provide strength through a sense of perseverance and community,” says Dr. Robyn Fivush, professor of psychology and associate vice-provost for academic innovation at Emory College in Atlanta, Georgia. “Adolescents who know more stories about their families and know these stories in more elaborate detail show higher levels of self-esteem and fewer behavior problems than adolescents who know both fewer stories and less detailed stories.”

Adolescents who know more stories about their families and know these stories in more elaborate detail show higher levels of self-esteem …

In her studies, Prof. Fivush focuses on the social construction of autobiographical memory and how certain narratives impact identity and coping. In 2010, she published the study “Do You Know…” The Power of Family History in Adolescent Identity and Wellbeing, detailing how knowing a variety of stories about a familial past affects adolescents’ emotional health. Her research substantiates what many have known for generations about sharing family history and grounding the youngest generations with stories of their past.

The Ancestor Effect

Research around genealogy’s beneficial effect on those who delve deep into the past and find themselves within its narratives has been reproduced not just with adolescents, but with older subjects. Dr. Peter Fischer and his colleagues at the Universities of Graz, Berlin, and Munich have observed what they have dubbed the “ancestor effect.” In their studies, they found that asking subjects to think or write about their recent or distant ancestors led them to perform better on a range of intelligence tests, including both verbal and spatial tasks. Furthermore, they found that subjects who thought of their ancestors operated more confidently, attempting more answers. The researchers even tested against the hypothesis that positive results were seen in subjects because they were thinking of people in their lives that elicit positive emotions. Subjects in control conditions who were tasked with writing about themselves or close friends before the tests did not display the observable benefits. Interestingly enough, it did not even seem to matter if students were asked to consider negative aspects of their ancestors—the ancestor effect still proved beneficial. “Normally, our ancestors managed to overcome a multitude of personal and societal problems, such as severe illnesses, wars, loss of loved ones, or severe economic declines,” Dr. Fischer explains. “When we think about them, we are reminded that humans who are genetically similar to us can successfully overcome a multitude of problems and adversities.”

Ancestry.com, the largest for-profit genealogy company in the world with sales to date of 14 million DNA kits globally, refers to research findings like these to appeal to its customers. “Passing down stories about family triumphs and struggles not only has the potential to strengthen a family’s bond, it yields so many other benefits,” representatives explain. “It turns out, when children learn about their families, they tend to be more self-assured, they experience less anxiety, and they are more resilient.”

The Cousin Connection

Whether one goes through a website or does the digging through primary resources themselves, researching family trees often leads to connecting with living relatives. After all, the deeper the roots reach, the greater the tree grows; the further back generationally one manages to research, the bigger the network of breathing descendants one will find.

Anecdotally, from the innumerable reviews on forums and blogs online, this historical exercise seems to breed interconnectivity, unity, and solidarity; knowing more about ancestors, their cultures, and migrations often redefines family, identity, and community. Newfound relatives can fill in the gaps that tracing known relatives creates. Though some of the stories people uncover are less inspiring than others—finding out an ancestor was particularly cruel as opposed to finding out that they were impressively magnanimous—the diversity of stories cultivates a nuanced understanding of one’s ancestry and builds a cohesive family narrative.

For many Armenians, cohesion is a painful affair. One year seems to have a monopoly on the Armenian story: 1915. Tales of sole survivors, orphaned grandparents with adopted surnames, and lineages lost to time still dominate Armenian narratives. “Many second- and even third-generation descendants of survivors themselves feel like orphans: no roots, no relatives, no uncles and great aunts—not by choice, but by force,” Dr. Ani Kalayjian, psychotherapist and professor of psychology at Columbia University, asserts. In her decades of extensive research on massive trauma, particularly in relation to the Armenian Diaspora, Kalayjian identifies a non-nuclear family structure as a part of a unique inheritance many Armenians recognize in their communities.

Valuing Extended Family

Identifying distant relatives as immediate family, and accepting cousins as siblings, is consistent with the organization of the pre-Genocide patriarchal gerdastan (extended family). From research based on the recall of Armenian survivors, Armenian families were organized into multigenerational communal groups of often more than 30 people under one roof. “The pre-Genocide Armenian family structure was formed through generations of family interactions in adaptation to historical conditions of oppression,” Kalayjian explains. “It provided shielding against periodic raids and persecutions, and was often the only available method to maximize the likelihood of a given individual’s survival.” Though the Genocide ravaged these family units, this structure was internalized and traveled with survivors into the diaspora.

When genealogy research uncovers long-lost relatives, family members that might have once lived under the same roof in the gerdastan are united. Not only do new cousins bring new perspectives and nuances to the family narrative, they have the potential to restore a family structure that has long been known to provide emotional and psychological support.

In their study Recollections of Aged Armenian Survivors of the Ottoman Turkish Genocide, Dr. Ani Kalayjian and Dr. Siroon Shahinian noted that survivors’ significant reliance on their social context, their families and communities, comprised their primary coping methods. “Their emotional links to the family, maintained if and when possible, were other ways Armenians survived, and gained strength and continuity in the midst of the chaos that transpired.” Though generations separate Armenians from the traumas of the turn of the 20th century, finding family through genealogical research still provides that continuity across generations of ancestors.

In Search of Roots

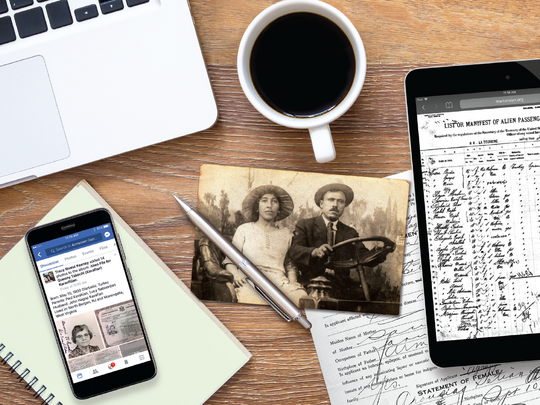

“In all of us there is a hunger, marrow deep to know our heritage—to know who we are and where we have come from,” wrote Alex Haley, author of Roots: The Saga of an American Family. “Without this enriching knowledge, there is a hollow yearning. No matter what our attainment in life, there is still a vacuum, an emptiness, and the most disquieting loneliness.” When Haley’s monumental novel was adapted to screen and broadcast across the United States in 1977, it drew an unprecedented estimated 140 million viewers, the largest audience ever for a televised miniseries at the time. A national moment of reckoning, the program was the first time the story of many Black Americans was illustrated in detail, depicting the brutal American history of slavery through one family’s generational experiences.

In all of us there is a hunger, marrow deep, to know our heritage—to know who we are and where we have come from.

To write the novel that started it all, Haley visited countless libraries and archives around the world, dedicating more than a decade to researching his own family history. The story he was able to trace inspired a movement, a collective interest in genealogy in the American imagination. “Almost overnight, the tracing of bloodlines, once seen as the privilege of the rich, was suddenly in vogue,” explains historian Barbara Maranzani. “Americans took advantage of many of the tools Haley had used; libraries across the country noted a significant uptick in visitors across all racial and ethnic lines and inquiries for genealogical records at the National Archives increased by a staggering 300 percent.” For millions of Black Americans, Roots and Haley’s research offered evidence that tracing ancestry was possible, that access to indigenous African identities was not entirely lost, and that family histories could be contextualized in a larger narrative.

More than four decades after Roots, Haley’s words ring true as more and more people look back through generations of ancestors, searching for their heritage. The long-running weekly PBS series “Finding Your Roots” with Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates has also fueled the movement, revealing the family trees of high-profile figures and celebrities from all ethnicities.

The fact that a century after the Armenian Genocide, in locations and generations far from the scene of the crime, the urge to know if someone is from Van or Marash, Sepastia or Dikranagerd, illustrates the yearning to be seen, to be contextualized in a larger narrative, to grieve collectively. “Working with the psychological impact of trauma as a group can restore a sense of reality, a catalyst exploring feelings, and challenging one’s emotions and beliefs,” Dr. Kalayjian asserts. “Groups give an opportunity to talk about and bear witness to the trauma, to grieve, to restructure the assumptive world, and to restore trust.”

Though many Armenians have grown up fiercely proud of their new voices, founding thriving Diaspora communities on almost every continent, the dearth of stories from before the 20th century has created a deafening silence. Yet, over the past two decades, that silence is being disrupted through genealogical research. As records once thought forever lost are being retrieved within seconds and the convenience of DNA testing is connecting long-lost relatives, the Armenian story is becoming ever more specific and nuanced. Details and observations of our family histories erase the emptiness, and, in the process, re-stitch the vast and varied tapestry that is the story of the Armenian people.