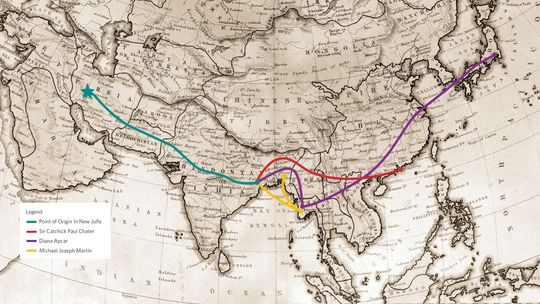

When the Silk Road reigned supreme with its vast network of trade routes stretching from the Far East to parts of Europe, the ancient Persian capital city of Isfahan figured prominently in the story of the first Armenian settlers in Asia.

Their destiny was inextricably tied to the commercial ambitions of one particular 16th-century Persian king Shah Abbas, who put them on a journey to the far corners of the East, ultimately leaving a trail of clues to their once strong presence and impressive image in the region.

It began with an elite group of Armenian traders living in historic Armenia under Ottoman rule. When their mercantile prowess caught the attention of the Shah, he decided to arrange for their relocation from their ancestral homes to serve his realm as the backbone of its economy. While his intentions were self-serving, the Armenians received something valuable in return: protection from Ottoman oppression and its constant threat of danger.

As a ready royal army of seasoned merchants and trustworthy negotiators, the Armenians enjoyed the favor and preferential treatment of their Persian rulers, enabling them to form a thriving community in the outskirts of Isfahan called New Julfa (corresponding to the Old Julfa of the Ottoman Empire, ultimately destroyed by the Persians).

There, they built up a solid base of wealth by which to erect magnificent Armenian churches and palatial mansions, as well as take up a brilliant tradition of decorative arts embellished with authentic Armenian motifs. Such splendor has been the object of awe by visitors and travelers to the region for centuries. And, through it all, this gem of a Christian Armenian suburb somehow remained exempt from the harsh treatment dealt to other minorities well into the 21st century.

Therefore it is no wonder that the family origins of three of Asia’s most notable and esteemed Armenian figures of the 19th and 20th centuries would be rooted in these enterprising, outward-looking forebears, who ventured eastward and decided to resettle and raise families in outposts as far from home as India, Myanmar, and China. Little did they know that their legacy of Armenian pride and global perspective would resurface in the fascinating life stories of Catchick Paul Chater of China, Diana Apcar of Japan, and Michael Martin of Bangladesh.

Sir Catchick Paul Chater

Hong Kong

In the latter half of the 19th century, an ambitious young Armenian from Kolkata, India arrived in Hong Kong, looking to seek his fortune in a city brimming with opportunity.

Born in Kolkata in 1846 to Armenian parents, Catchick Boghos Asvadzadoor was one of 13 children of Chater Paul Chater, a member of the British India civil service, and his wife Miriam. Young Catchick was only seven when he and his siblings were orphaned in 1853 when Miriam passed away at age 44.

Chater went on to be educated at La Marinière School Kolkata between 1854 and 1864. Upon graduation, he decided to visit Hong Kong and stay with his eldest sister Anna and her family. Seeing the limitless potential of the city, he quickly found employment as a bank clerk and decided to settle in Hong Kong.

Over the next few decades, Chater, a visionary with sharp negotiating skills, singlehandedly transformed the city into an economic powerhouse. He founded a string of successful companies and owned a wharf, iron and coal mining enterprises, as well as cotton-spinning factories.

He collected valuable Chinese art worth millions of dollars in today’s valuations. He was the quintessential representative of Armenians in 19th-century Asia, known for his business acumen, his philanthropy, and his global perspective.

In 1889, the Praya Reclamation scheme, a large-scale land reclamation project of the Hongkong Land company in colonial Hong Kong was carried out by Chater and James Johnstone Keswick, laying the foundations of the financial hub of the Central Hong Kong of today. Chater also owned prime real estate in key locations in Canton (present day Guangzhou) and Macau, in addition to a large tranche of valuable waterfront property in Singapore for which he had big plans to develop. In 1896, he was appointed as one of the first of two unofficial members of the Executive Council of Hong Kong.

During this same period, Chater and his business partner H.N. Mody formed the Société Française des Charbonnages du Tonkin, which developed coal mines in North Vietnam—all with the intention of supplying coal to his own company Hong Kong Electric. It was described as one of the only truly successful commercial undertakings in the entire history of then-French Indochina. In October 1891, a grateful French government awarded Chater the prestigious Chevalier de la Lègion d’Honneur.

In 1899, Chater adroitly negotiated a deal in which the government of Hong Kong would donate a public space to the tune of 67,000 square feet and Chater would finance the construction of the St. Andrews Church in Kowloon. The foundation stone was laid in 1905. The church continues to thrive to this day.

A generous philanthropist, Chater also donated to the University of Hong Kong, St. John’s Cathedral, and other churches. A section of Hong Kong still bears the Chater name, including streets, squares, and houses, such as Catchick Street, Chater Road, and Chater Garden.

Sir Catchick Paul Chater was knighted in 1902. He passed away at age 79 in Hong Kong, survived by his wife Maria Christine Pearson and his nephews. He bequeathed his mansion Marble Hall and its entire contents, including his unique collection

of porcelain and paintings, to Hong Kong. The remainder of his estate went to the Armenian Church of the Holy Nazareth in Kolkata, which runs a home for Armenian elderly named the Sir Catchick Paul Chater Home. He was interred at the Hong Kong Cemetery.

By Liz Chater

Diana Apcar

Japan

It’s a little known fact that Sir Paul Chater and Diana Apcar were cousins. Their common ancestor was Catchick Arrakiel, Sir Paul being his great grandson and Diana being his 2X great granddaughter.

Possibly the first woman to ever be appointed to any diplomatic post—certainly the first in the 20th century—Diana Apcar was a zealous advocate for the oppressed, an indefatigable crusader for human rights, and a champion of the Armenian people. Her convictions were expressed in a letter she wrote to then U.S. President Howard Taft during the height of the refugee crisis resulting from the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

“The annals on that presidential chair on which you sit are clear and bright as the noonday sun,” she wrote, “turning over the pages of their brightness, I am encouraged to address you.” Dedicated to saving her people and desperately seeking to alleviate suffering, Apcar refused to let her distance from Armenia translate into apathy. “You will agree with me that the meanest and humblest of God’s creatures has a right to speak the truth,” she reasoned with Taft, “and greatest is the right to speak the truth, when it is spoken in the cause of murdered, outraged, and misery-stricken humanity.”

She was born Diana Gayane Agabeg in Yangon, Myanmar (formerly Rangoon, Burma), on October 12, 1859. Her father was born in Kolkata, and her mother born in Yangon. She came of age in Kolkata, the youngest of seven children. Her marriage to Apcar Michael Apcar in 1889 would introduce her to the global business the Apcar family had built over generations—involved in shipping, import/export enterprises, and rice farming throughout South Asia and the Far East. Apcar & Company would motivate the young couple to settle in Yokohama, Japan soon after the birth of their first child.

When Apcar arrived in Japan, she was an aspiring writer, already fluent in Armenian, English, and Hindustani. Settling in Yokohama, she mastered Japanese. Though the city was alive with opportunity for the new family, a series of tragedies befell the Apcars. Of the five children the family was blessed with, only three survived childhood. After two bankruptcies, Michael Apcar suddenly died in 1906, leaving his wife with three young children in a foreign land.

Assuming the burden of restoring the family business while raising her children, Apcar proved herself a clever and versatile negotiator. When her son was old enough to inherit the business, she focused her attention on her passions: literature and diplomacy. Publishing writings both domestically and internationally, in all of the languages she wielded, Apcar’s political articles, literature, and poetry were printed in various journals, such as the Japan Advertiser, the Japan Gazette, Far East, and New Armenia. She cultivated a voice of solidarity with the oppressed people of the world, acutely aware of the violence besieging Armenians in the crumbling Ottoman Empire. By 1920, Apcar published over nine books focused on international relations, namely the scourge of imperialism, the potential for world peace, and the responsibility of those in power to act judiciously. She took up the Armenian cause fervently.

Apcar did not just espouse lofty political ideologies of peace, she wrote to everyone and anyone in a position of power—presidents, prime ministers, ambassadors, humanitarians—who could do something to stop the massacre of Armenians and provide aid to survivors. Her words translated to work as she tirelessly endeavored to appeal for safe haven on behalf of thousands of refugees all over the world. Her support for the Near East Relief was particularly notable.

Apcar’s relentless efforts led Japan to become one of the first nations to recognize the independence of the newly formed Armenian Republic in 1920. The same year, Diana Apcar was appointed Honorary Consul to Japan by Hamo Ohanjanian, the Republic’s foreign minister, making her the first Armenian woman diplomat, and the first woman diplomat in the 20th century.

While her tenure concluded with the sovietization of Armenia, her activism and diplomacy on behalf of her people never did. Though she lived out her life in Yokohama, Japan, a resourceful diplomat, a prolific literary figure, and a woman of insurmountable faith a century ahead of her time, Apcar remained devoted to a free, prosperous Armenia.

By Nana Shakhnazaryan

Michael Joseph Martin

Bangladesh

Though there is no consensus on when the first Armenian came to Dhaka, Michael Joseph Martin was certainly known as the last Armenian to leave it. Officially becoming the caretaker of the Armenian Apostolic Church of Holy Resurrection in 1986, Martin is credited with protecting the Armenian Church in Dhaka through three often tumultuous decades in Bangladeshi history. “Without him,” Martin’s successor Armen Arslanian explains, “Armenians would have lost this historic place of worship, this vital connection to our ancestors, indefinitely.”

The youngest of nine children, Michael Joseph Martin was born Mikel Housep Martirossian in Yangon, Myanmar, in 1930, when it was still the Burmese capital of Rangoon. The Martins had invested heavily in the city, operating a lucrative trade business, and so they, like many other Armenian families in Burma at the time, were integrated into the fabric of Rangoon. Coming of age in a large family, Martin enjoyed a relatively peaceful childhood in a city that would soon be swallowed by war.

December 1941 marked the end of an era in Rangoon. As imperial powers wrestled for control throughout the world, the city was center stage in the South-East Asian Theater of World War II. Before the Japanese officially occupied the city, bombs rained on Rangoon. Because the Martins owned property adjacent to an important part of the city’s railway system, a site known for transporting munitions to China, Japanese planes would fly low looking to disrupt the cargo. Just 11 years old at the time, Martin still remembers how Burmese government officials came to visit his father after a bomb destroyed their home tennis court. “They said it was the third largest bomb dropped in Burma at the time,” he recalls. “The crater created was so deep, and there was shrapnel everywhere. We were instructed to leave.”

As Japanese attacks on the city escalated, the family made plans to evacuate to India, where some of the Martin clan had already settled. The journey from Rangoon to Kolkata by ship was treacherous—Martin recalls the crew painting the vessel with camouflage as they sailed on the high sea—but five days later, starved yet relieved, they docked in the Bay of Bengal. The Martin family reassembled in Kolkata and their youngest son continued with his schooling at the Armenian College, where he became known for both his musical and athletic talent.

With a childhood split between two cities, Martin became adept at negotiating and followed his father into the family firm in Kolkata, Martin & Sons. Soon venturing out on his own, he departed from the family trade business to pursue the jute industry, working his way through the ranks at various companies and developing himself as a versatile businessman. Martin even dabbled in the restaurant business, opening Cafe Stadium, which routinely catered to government officials and international traders. It was his hunger for bigger and better opportunities that would take him to East Pakistan in the early 60s, where he would meet his wife Veronica Gonsalves and start his family in the soon-to-be-declared democracy of Bangladesh.

Though the family settled in Kolkata, Bangladesh would continue to call to Martin. In 1986, as a congregant of the Armenian Church in Kolkata, he was made aware of the perilous state the Armenian Church in Dhaka was in. In the hands of an indifferent, non-Armenian caretaker, the church had been neglected for years. With its community gone, infrastructure crumbling and centuries-old graves left unprotected, the church was abandoned, neighboring an unofficial dumping ground that channeled raw sewage and waste onto its grounds. When the caretakers of the Armenian Church in Kolkata were notified that a group of foreign investors were looking to take control of the property, they asked Martin to go to Dhaka and protect the church grounds. This experience would transform him into the fiercest advocate the church had ever seen in Bangladesh.

Successfully pushing out the foreign investors with his diplomatic connections, Martin began massive efforts to renovate and restore the church to its former glory. Because the jaded former caretaker prohibited local laborers from working on the church, Martin contracted labor from Khulna to build, paint, and plaster. Though threatened with force, and often with local curses, he refused to abandon the church and relocated to the city with his family. “I took over the care and responsibility of the Armenian Church in Dhaka because I considered it my duty,” Martin explains. “The blessings, guidance, and protection I received along the way convinced me I had chosen the right path.”

On January 6, 1987, Christmas Service enlivened the Armenian Church in Dhaka for the first time in decades. Delivered by a priest from the Church of England and attended by a mixed congregation of both locals and foreigners, the service was evidence that Michael Joseph Martin succeeded in saving so much more than just the church grounds. With his dedication to restoring the spirit of the Armenian Apostolic Church of Holy Resurrection, Martin salvaged a priceless piece of both Armenian and Bangladeshi history.

In 2014, Michael Martin relinquished his responsibilities as caretaker to Armen Arslanian. For his decades of service, the last Armenian in Dhaka was recognized with the St. Nerses Shnorhali Medal by Catholicos of All Armenians Karekin II.

By Nana Shakhnazaryan