At the forefront of today’s Armenian genealogical movement are many unsung heroes who have taken it upon themselves to collect and transcribe historical Armenian records and deliver them to the masses. Most are hobbyists with other professions and volunteers who have made it their life’s work to give Armenian family history access, accuracy, and meaning to successive generations. While not all of the leaders and innovators involved in solving the mysteries of our family histories are accounted for in this survey, the profiles herein are instructive as to how genealogy can change our understanding of ourselves, our families, and the stories that write the wider history of Armenians through time. With every breakthrough, connection, and discovery, they enrich the Armenian identity, both personally and collectively.

The Technovator

Mark Arslan

Cary, North Carolina

Armenian Immigration Project

Some of the most curious and determined researchers of family trees are those who are of mixed ancestry. Mark Arslan is one such enthusiast, a second generation Armenian-American (one quarter Armenian through his paternal grandfather), who began his journey at age 11 to become one of the leading pioneers of Armenian genealogy in the digital age. There is poetic symmetry in the fact that someone so dedicated to cultivating family trees coincidentally earned a degree in forestry from Oregon State University.

His enchantment with genealogy began at age 16, when Arslan took a self-study computer programming course and realized that this technology could be used to organize his data. Arslan, who went on to enjoy a successful 35-year career as an IBM sales executive, created his first piece of genealogy software in 1973, which allowed him to research projects of his own. He studied microfilm reels of old census records and wrote letters to elderly relatives to learn of his own family history.

By the 1990s, the internet gave Arslan the impetus to engage with newly emerging web resources; in particular, early online forums revolutionized how he could connect with people and exchange information at a speed never before seen. About a decade later, the online integration of the Ellis Island ship manifests proved to be a breakthrough for him. After finding his own relatives in these records—his grand-father had arrived in the United States from Keghi, Erzurum in 1906—he expanded to researching all immigrants from Keghi and uploaded spreadsheets of information from which others could benefit. This was the modest start of something huge.

By the mid-2000s, as the internet’s capabilities grew, he broadened his scope from Keghi to include all Armenian immigrants to the U.S. and Canada prior to 1930, inspired by Robert Mirak’s and Isabel Kaprielian Churchill’s works on Armenian immigration to the two countries. Far beyond Ellis Island, there were over a dozen active seaports processing Armenians at the time, so Arslan created his own online portal with data captured from these ship manifest images. Going live with 20,000 entries, the Armenian Immigration Project was launched in 2011.

Today, the website goes beyond immigration. It integrates numerous other primary sources, including naturalization records, censuses, military and vital records such as births, deaths, and marriages, even transcriptions of post-Genocide newspaper listings of survivors searching for lost relatives in hopes of reuniting with them at the end of World War I. The project includes abstracts with citations of over 133,000 primary records with 1,000 to 2,000 more added each month.

While mainly useful to American-Armenians, the data is so expansive it also accounts for persons from every corner of historical Armenia. Other ingenious functions are the grouping of surnames with variations in spelling and the ability to sort records by many variables, including birth place, destination address, and surname of the person being joined in America. As a result, a researcher with ancestry from Sivas (Sepastia) for example, can search the database for every immigrant born there. This cannot be done through the Ellis Island database nor any other website.

Today, Arslan is a main figure in the Armenian Genealogy Facebook group, using his database to assist members with their family history questions and to support them in their search. He has helped uncover entire lineages, identifying previously unknown half-siblings and even tracking down biological parents. He is hopeful that he has inspired a community that will grow and evolve in the future, with an intimate understanding of their ethnic past.

The Researcher

Liz Chater

London, United Kingdom

Chater Genealogy

In a quiet hall of the British Library in early 2000, Liz Chater sat mesmerized by the thin, time-stained cursive of Armenian letters at her fingertips. She was eager to trace back some of her family history, armed with the little information her mother could give her and her father’s mysterious surname. “There was nothing in my world at the time that indicated to me that I was anything but British,” Chater admitted. Yet, on that first trip, she would trace back five generations of Chaters to Dhaka, Bangladesh—and, soon after, would stumble upon a great-great-great-

great-grandfather with an Armenian name. It turned out Liz Chater was Armenian.

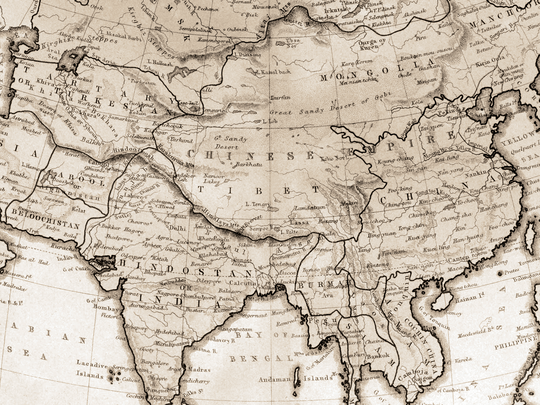

That fortuitous first trip would serve as the catalyst for nearly two decades of intensive research into the rich, unexpected and often unexplored Armenian history of Southeast Asia. Having pieced together her family tree and solved the mystery of her Chater ancestry, she has used her curiosity to help others in their search. From Mumbai to Agra, Chennai to Kolkata, she has delved into the annals of each city, following the Armenians that made their way ever further east through the centuries.

Painstaking as it is to transcribe 17th-century wills or photograph hundreds of ancient graves, Chater pored over these records in an effort to reconstruct the lives of little-known Armenian diasporas by documenting and publishing her findings online. With no formal academic background as a historian, she pursues countless individual stories at a time, occasionally relying on the insights of a network of dedicated scholars, researchers, and hobbyists. Her mantra breaks through any walls she hits along the way: “If this were easy,” she smiles, “someone would have already done it.”

Fate scattered Chater’s Armenian ancestors so far east they managed to avoid the Ottoman tyranny that would culminate in the Armenian Genocide. The knowledge of the diasporas they represent diversifies the Armenian experience, and the individual genealogical research that Chater performs chips away at the monolithic conception of Armenian history and identity. A stateless people for centuries, Armenians thrived in every civilization they settled in. Now, these histories are being recovered, along with much more.

“Before starting my search, I was in no-man’s land,” Chater reflects. “Doing this work, I discovered family, a way of life, a country, a people I didn’t know about.”

Before starting my search, I was in no-man’s land. Doing this work, I discovered family, a way of life, a country, a people I didn’t know about.

The Redeemer

George Aghjayan

Worcester, Massachusetts

Hidden Armenians

While DNA testing might seem like a fun way to learn whether you are more English or Swedish, or if those old family stories about a Native American ancestor are true, the stakes and possibilities go far beyond what those ubiquitous TV commercials might lead one to believe. For Armenians, it has, in the words of George Aghjayan, one of the leading proponents of Armenian DNA testing, the possibility to “bring ancestors back from the dead.”

Like most Armenians, Aghjayan’s family lost numerous relatives to the Genocide or was separated during the deportation caravans sent out in waves across the Ottoman Empire. Even those who might have left as a group were subject to kidnapping and other means of separation, never to be seen again by their surviving relatives and presumed dead. In reality, not all of these lost relatives had actually perished, as the phenomenon of “hidden Armenians” surfacing in modern-day Turkey shows.

Aghjayan would make frequent trips to the region known as Western Armenia, and meet these “remnants of the sword” as they have long been called in Turkey, despite Turkish government denials that such mass killings ever took place. Those aware of relatives that survived over 100 years ago rarely knew more than their Armenian ancestors’ first names, making identification impossible. Thus, Aghjayan became involved with the Armenian DNA Project through FamilyTreeDNA, appreciating its capacity to make connections via genetic markers. How much DNA is shared between two people can determine their approximate relationship, so the more Armenians in the database, the more sets of data by which to find potential matches. Aghjayan hoped that this new technology might reconnect Armenians that had long been denied their true identities. What he didn’t expect is just how close to home it would reach.

Just about every Armenian who joins the DNA Project will immediately match with at least some fourth or fifth cousins, people who share a common ancestor seven or eight generations back, which is further than most Armenians can trace their families. While this information is intriguing at face value, it is not as helpful in rebuilding a family tree when it is impossible to make specific connections. Aghjayan was in the same position until 2015, when a month after receiving his DNA results, the surprise he was waiting for arrived—a match with a first or second cousin.

Not only that, Aghjayan’s possible cousin was living in Turkey, someone obviously unknown to his family. So Aghjayan e-mailed him immediately. The reply was shocking.

The mother of the DNA match was born Armenian in the village of Maden, the same town as Aghjayan’s great-grandmother. The newfound cousin recounted the story: Two sisters were on the deportation march when a cavalry officer decided to marry the older one. She agreed on the condition that her younger sister could live with them as well. This sister would later marry a Muslim man, and one of her sons was Aghjayan’s DNA match. The story rang all too true because the names of the parents of these orphaned girls matched those of Aghjayan’s father’s great-grandparents. They were on to something.

Reviewing his notes from conversations with relatives 25 years prior about his great-grandmother Nevart, two words Aghjayan had jotted down stood out: “another sister.” The DNA evidence was clear, “another sister” referred to a lost sister of his great-grandmother who had survived the Genocide unbeknownst to his family, likely the mother of his DNA match.

He and the match eagerly reconnected, sharing photos and family stories and making plans to meet in person. As Aghjayan sums up: “The people in this story remain victims of genocide, but they no longer are tallied amongst the dead. The 1.5 million has been reduced by two.”

In subsequent travels to the region, Aghjayan arranged for other hidden Armenians to be tested to add them to the database, an initiative he plans to continue. Says Aghjayan, “Every reconnection is a reclamation of what was lost.

The Reuniter

Janet Achoukian Andreopoulos

Phoenix, Arizona

Armenian DNA Project

Janet Achoukian Andreopoulos was introduced to DNA testing through the Armenian DNA Project, founded by Mark Arslan and co-administered by Peter Hrechdakian, a businessman from Belgium and Hovann Simonian, a political scientist from Switzerland. The site recognizes the lack of Armenian participation in commercial genetic databases and solicits Armenians to submit their DNA to build a robust sample size. Not only did she urge her father to take the test to help expand the site’s database of Armenian DNA but she also started a campaign encouraging others to take the test. She was particularly interested in finding people with roots from her ancestral village of Evereg, having already created a traditional family tree of everyone she could find from there. Using DNA, she was able to validate some of those known connections while discovering new ones. For example, two of her childhood Armenian friends had grown up together in New York but had no idea they were related until taking the test.

Andreopoulos, despite the responsibilities of a full-time job and mothering two teenage sons, volunteered to serve as a co-administrator at the Armenian DNA Project, helping others learn their genetic history and discover long-lost relatives. Like the other volunteer genealogists profiled, Andreopoulos spends numerous hours a week through platforms such as the Armenian Genealogy Facebook group helping others looking to solve family mysteries or to piece together their family story.

Sometimes, an American or European will come to Andreopoulos with their DNA test results saying they had no idea they were Armenian, thus creating a whole new category of “hidden Armenians” beyond those in Turkey. Due to a variety of reasons, such as being adopted, being the child of an adoptee, or numerous other cases of hidden or mistaken paternity, DNA tests are revealing their Armenian identity and all the questions that come with this new information. Besides helping them discover their biological families, Andreopoulos has also helped these newfound Armenians connect with their ethnicity. One such woman whom she helped connect with newly discovered Armenian relatives signed up for Armenian language classes. Another woman was able to reunite with her biological father and they attended Armenian church services together.

One such case is that of Catie Webster. Her mother, who was adopted at birth, had long suspected that she was Armenian based on her features, but never had confirmation until taking a DNA test. When the results came back, it confirmed her intuition, but there were also biological Armenian relatives with whom they could potentially establish a line of communication. Eventually, Webster connected with Andreopoulos, who was able to put her in touch with close biological relatives.

“This effort is part of our identity as Armenians,” says Andreopoulos. “Family trees help preserve Armenian life and culture. Every Armenian is a piece of one huge jigsaw puzzle, which we now have the tools to solve together.”

Family trees help preserve Armenian life and culture. Every Armenian is a piece of one huge jigsaw puzzle, which we now have the tools to solve together.

The Networker

Tracy Keeney

Kansas City, Missouri

Armenian Genealogy Facebook Group

As described in the introduction to this article, Tracy Keeney’s story deeply resonates with a unique group of Armenians—those have been effectively isolated from their Armenian pasts, who then suddenly discover a connection that spurs them into action to explore their ethnic identity by connecting with family members.

Keeney, whose mother is Armenian, was well aware of her Armenian heritage, but, growing up in a military family, the constant relocations across the United States prevented exposure to Armenian community life. Nevertheless, after finding a mysterious photo in her grandmother’s closet, her curiosity led her to find 97 names to pursue further, reaching out to as many as she could with the photograph. In less than 10 days, Keeney’s phone began to ring off the hook. Among the first callers was a woman who had grown up with the same family portrait displayed in her home. One of the children depicted was the caller’s father. She also recognized the others as her grandparents, aunts, and uncles. The caller turned out to be the granddaughter of Keeney’s great grandmother’s older brother.

Today, Keeney is the founder and administrator of the largest Facebook Group on Armenian genealogy—with over 10,000 members from across the globe actively engaged in collaborating with fellow members to solve mysteries of their familial past. Keeney founded the group in late 2013, starting with just her friends and family. She soon found herself spending hours a day sorting through the stories of hundreds more seeking to join. “It was wonderfully strange how so many of us who had felt so isolated, like we were the only branch of our families that survived, were discovering that we weren’t the only ones. Our families were much bigger than we knew,” remarks Keeney.

Online dialogues sparked the next step: organizing a global conference offline, so that genealogy enthusiasts could gather in person, become acquainted, swap stories, and guide others to break down those brick walls in their family sagas. The first conference was held in Watertown, Massachusetts, in April 2016; while the organizers had estimated 80 people would attend, over 300 arrived, from as far as California and the United Kingdom. It is now an annual event, held in Detroit, Michigan, in 2017, and Ramapo, New Jersey, in 2018. The 2019 conference will be held this autumn in Los Angeles, while smaller workshops are also held periodically in other parts of the country. As Keeney reflects, “Even though it’s generations later, the impact of finding family members, even those you didn’t even know existed before, is something that can only be truly understood by those who’ve experienced it.”

The Scientist

Prof. Levon Yepiskoposyan

Yerevan, Armenia

The ArmGenia Project

One of the pre-eminent names in Armenian DNA studies, Prof. Levon Yepiskoposyan, is an academic from the Institute of Molecular Biology at the Armenian Academy of Sciences whose passion for Armenian genealogy has taken on new dimensions in its application. Through his leadership, the ArmGenia project was established to study Armenians around the world, based on their origins in historical Armenia and Ottoman Turkey. From this perspective, the mission has implications for national security.

“By collecting someone’s DNA, we are also gathering that of their ancestors. It’s a common misperception that Armenians are relative newcomers to the region, which is exploited to disenfranchise us of our historical claim to these lands. We need physical evidence to refute this with internationally verified studies to demonstrate the presence of Armenians in this region. If and when the DNA is very similar, it proves that Armenians are ancient inhabitants of the land and not recent invaders as Azerbaijan falsely asserts in order to invalidate the Armenian claim to it,” Yepiskoposyan notes, referring specifically to the Artsakh question. In fact, this longstanding issue gave him the impetus to organize an archeological dig there to find traces of ancient Armenian DNA.

If and when the DNA is very similar, it proves that Armenians are ancient inhabitants of the land and not recent invaders as Azerbaijan falsely asserts in order to invalidate the Armenian claim to it.

Prof. Yepiskoposyan goes on to say that the participation of all Armenians is essential. “The more Armenians who provide their DNA samples, the more precise the results will be. With each generation we lose this original genetic information as it becomes more and more mixed, so we need to act now. We are preserving this DNA data for future generations of scientists who will have more powerful equipment to extract even more information from these samples.

He also notes that “current research shows that Armenian DNA was isolated to itself for 4,000 years, so we can test if any of the many invaders through the region left genetic traces in our gene pool over that period. So far, there appears to be very little of this. It has very profound ethnic and psychological meaning for us.”

The project, while based in Armenia, has an international scope. The professor explains: “We need the DNA of western as well as eastern Armenians, and to test westerners you must go to the Diaspora, specifically the elderly, who can trace their bloodline to just one village. Their testimonies and their DNA samples are urgent, as time is obviously running out.”

To date, most of the data has been collected within Armenia. Unlike with other genealogy projects, those who provide DNA samples do not receive reports; they are just populating the database. “What we call mapping is simply collecting data from individuals whose ancestry is traced to a relatively small location within the Armenian homeland—focusing on areas no more than 50-100 kilometers distance from each other,” Prof. Yepiskoposyan points out.

To this end, ArmGenia has charged supporters from the Diaspora, such as Kevork Khrimian of New York, with the specific task of collecting samples from Armenian clusters along the New England-Mid-Atlantic corridor of the United States. “Most of this segment of the community are in their 80s and typically born in the U.S., but their parents often came from the same cluster of villages in areas such as Sepastia, Kharpert, or Dikranagerd. This population of DNA is quickly being lost as subsequent generations are mixed with Armenians from other areas or non-Armenians, and so we are losing our ability to know the genetic makeup of Armenians from specific villages. The reason why we’re collecting from the U.S. is that western Armenians in a regionally pure form are rare in Armenia, though there are still populations in Armenia which come from places like Van, Mush, and Sassoon, but no further west into the original Armenian homeland.”

ArmGenia aims to map the entire Armenian homeland. “Many people don’t realize that more than half of Armenia’s population are descendants of post-Genocide refugees from places mentioned like Van and Taron. Another large group are the descendants of repatriates from Persia after the Russian conquest of Armenia in the early 1800s. As a result, the population here in Armenia is quite mixed today, just as it is with the younger generations of the Armenian-American population,” says Prof. Yepiskoposyan. “This makes it difficult to get a clear sense of the DNA makeup from most provinces of modern-day Armenia.”

The ultimate goal of ArmGenia is to draw a genetic atlas of historical Armenia to reproduce the rich spatial mosaic of the Armenian gene pool, which originated and flourished for several millennia in the expanse of the Armenian Highland.

Starter Guide to Tracing Armenian Family Trees

Searchable Websites

These database websites can be used to start a personalized search by different variables and categories of data, depending on the scope of the searchable content. Some sites are free; others subscription based.*

Free Global Databases

FamilySearch

familysearch.org

Find a Grave

findagrave.com

Subscription or Fee-based Databases with DNA Testing Services

23andMe*

23andme.com

AncestryDNA*

ancestrydna.com

FamilyTreeDNA*

familytreedna.com

MyHeritage*

myheritage.com

Free Armenian-related Databases

Armenian Immigration Project

markarslan.org/ArmenianImmigrants/shiplists.html

Armenian DNA Project of FamilyTreeDNA.org

familytreedna.com/groups/armeniadnaproject/about/background

Chater Genealogy

chater-genealogy.com

Western Armenians

westernarmenia.weebly.com

Networking Opportunities

Collaboration is an important facet of original family-tree research and joining or participating in these networks can yield surprising results through shared stories, exchanging research tips, and finding helpers such as translators.

Armenian Genealogy Facebook Group

facebook.com/groups/armeniangenealogy

Armenian Genealogy Conference

armeniangenealogyconference.com

Contextual Research

These resources offer the genealogical researcher a wealth of contextual background about Armenian life in the pre-genocide period, adding color, nuance, and perspective to one’s family stories. In some cases, clues to unsolved family mysteries can be found through archives, oral testimonies, books, photos and newspaper ads, provincial dress and folk crafts, surname derivations, and other cultural items collected, curated, and managed by dedicated specialists.

AGBU Nubar Library

agbu.org/educatiom/library-research-center

Armeniapedia

armeniapedia.org

Armenian National Institute

armenian-genocide.org

Dictionary of Armenian Surnames

armeniapedia.org/wiki/Introduction_to_Dictionary_of_Armenian_Surnames

Gomidas Institute

gomidas.org

Houshamadyan: Ottoman Armenians Project

houshamadyan.org

National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR)

naasr.org

Project Save

projectsave.org

Zoryan Institute

zoryaninstitute.org

Scientific Projects

The science of Armenian genealogy through DNA testing and innovative research methods can add new dimension to understanding Armenian history, migration patterns, ancient DNA, biology and diseases, and other facets of identity formation and genetics.

ArmGenia

armgenia.am

David Reich Lab/Harvard Medical School

reich.hms.harvard.edu

For more information on how to trace your family genealogy, click here.

Banner photo by Barton Wilder; Liz Chater