Nineteenth century Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle once proclaimed that history is the combined biography of great men. While indeed the role of remarkable individuals can determine the future course of nations, Carlyle’s statement is but a half-truth, and for a historian himself, an egregious one at that.

For history of course, includes the combined biography of both great men and women. Throughout the ages, whether it was Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, or Marie Curie, women have played a decisive role in shaping the fortunes of empires, leading social transformation, and advancing scientific progress.

The history of France is renowned for the heroic and intellectual exploits of many great female historical figures, from Joan of Arc to Simone de Beauvoir. Among those who inspired social change and impacted the world around them, there are three Francophone women of Armenian origin whose leadership, intelligence and courage helped define a pivotal moment in French history and left a lasting legacy.

A powerful and wise medieval Queen who transformed Jerusalem, a leading novelist and intellectual who rallied against social injustice, and a fearless and outspoken resistance fighter who refused to accept the Nazi occupation of France, these three influential female pioneers inspired change and each served as a voice of social leadership. They were not afraid to challenge convention and defy expectations of a woman’s role in society. In so doing they became role models by breaking down barriers and demonstrating that women were just as capable in leadership roles as their male counterparts. The success and recognition they achieved on their own accord in male-dominated realms set an important example for other women of their generation.

While they each faced and overcame challenges unique to their respective era, all three women shared a common bond of Armenian heritage. Whether explicitly or implicitly by virtue of their fame, these leading ladies also played a significant role in bridging French and Armenian cultures, conveying the importance of the Armenian world throughout Europe and beyond, and fostering a close connection between two nations that persists today.

Here are their stories.

Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem

By Jirair Tutunjian

Until the Crusades Franco-Armenian relations had been between individuals. The Crusades changed that when Cilician Armenia and France established political, military, cultural, religious, and marital relations. Off and on, the two states were allies, competed for influence in the Middle East, and their nobility intermarried. The first two Crusader queens of Jerusalem (Arda and Morphia) were Armenian while the third—Melisende—had a French father and Armenian mother. It’s no exaggeration to say that she was the most remarkable woman of the Crusader era.

What made Queen Melisende (1105-1161) stand out from Levantine European noble women? Contemporary historian William of Tyre wrote she was of “great wisdom who had much experience in all kinds of secular matters…It was her ambition to emulate the magnificence of the greatest and noblest princes and to show herself in no way inferior to them.”

Historian Jonathan Phillips (Holy Warriors, 2009) wrote: “Queen Melisende’s powerful and charismatic personality cast its influence across the Levant for over two decades—a remarkable achievement in the most war-torn environment in Christendom and in such a male-dominated age.”

Like her French father (King Baldwin II) she was tall and slender. Like her Armenian mother (Queen Morphia) she had large dark eyes and strong brows. William of Tyre wrote that she was “beautiful, wise, sweet and compassionate.”

Although she lived in turbulent times, her near thirty-year reign was relatively tranquil in external affairs. To guarantee the security of her north and east borders, she had befriended the powerful Saracen ruler of Damascus.

Because their mother had died while they were children, Melisende acted as surrogate mother to her three younger sisters. She helped arrange the marriages of Alidz to Prince Bohemond II of Antioch and of Hodeira to Count Raymond of Tripoli. Melisende’s ulterior motive was to strengthen her family’s network.

Nonetheless, most of Melisende’s travails were family related. Since her parents had no son, she—the eldest of four daughters—was designated to succeed her father. King Baldwin was confident he could tutor his daughter to become an effective ruler.

To secure the future of his kingdom, her father needed the patronage of Louis VI. So as to enter into that king’s inner circle, Baldwin asked the king to pick a Frenchman as Melisende’s husband. The king chose Count Fulk of Anjou, a wealthy warrior. Putting the interests of the kingdom ahead of her preference, twenty-two-year old Melisende was married off to a man of lesser refinement who was twice her age.

After King Baldwin died Fulk tried to undermine Melisende’s authority: he ignored the agreement he had signed which said he would be co-ruler with Melisende. To stain Melisende’s reputation, Fulk also encouraged rumors that she was in love with her distant cousin, Count Hugh of Jaffa. As a result, the population was polarized. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Melisende formed an anti-Fulk bloc of church leaders who disliked Fulk’s fawning gaggle of sycophants. She also won over noblemen who resented that “Fulk had overly favored newly arrived Frankish Crusaders from Anjou over the native nobility,” wrote William of Tyre.

Then a deus ex machina intervened: an attempt was made on Count Hugh’s life. Fulk was accused of engineering the assassination. The botched attempt tipped the balance of power to Melisende. Seeing the tide had turned against him, a chastened Fulk began to consult his wife even on trivial matters. A few years later Fulk was killed when he fell off his horse. Melisende became sole ruler since her elder son (Baldwin III) was underage.

With the threat to her power removed, Melisende devoted herself to urban renewal. A few years earlier she had persuaded Fulk to grant lands to the Holy Sepulchre, establish a scriptorium, and build the St. Lazarus Abbey. She now built markets in Jerusalem and gave large “endowments to Our Lady of Josaphat, the Templum Domini, the Catholic Order of the Hospital, the leper hospital of Saint Lazarus,” says historian Bernard Hamilton (“Queen of Jerusalem”). She built the St. Anne Church and another one over the tomb of Virgin Mary. Melisende granted lands to the Armenian Church which became the nucleus of the Armenian Quarter.

She also helped establish a scriptorium to produce illuminated manuscripts. The pièce-de-résistance of the scriptorium’s was the ornate Melisende Psalter. Historian Malcolm Barber (“The Crusader States”) said, “Both the Melisende Psalter and a near-contemporary missal made for an Augustinian house in Jerusalem show the importance of the Armenian world, in the former case in the use of color, and in the latter through the scribe who seems to have been Armenian.”

Melisende had a passel of advantages which enabled her to undertake urban development projects. Because she was intelligent, dominating and charismatic, she could persuade people to see her way. She was also admired for her patriotism. The clergy supported her because she had a tight grip on the Church while the nobles backed her because she was the daughter of a king they admired. Patriarch William was a life-long supporter. His successor (Patriarch Fulcher) was appointed by Melisende. Powerful noblemen (Philip of Nablus, Prince Elinand of Tiberia, and Viscount Richard the Elder) were her “lieutenants”. They stood by her from her coronation, through the conflict with her husband and later with her son.

The commander of the army (Manasses of Hierges) was Melisende’s first cousin. She also enjoyed the backing of the powerful High Court, the royal council composed of nobles and church leaders. The court had legislative and judicial powers. Following her quarrel with her son the pro-Melisende court divided the country into two regions, giving the rich Samaria and Judea, including Jerusalem, to Melisende.

Finally, Melisende proceeded with her projects without objections from the church because the projects were mostly ecclesiastical.

Her focus on urban development didn’t mean that she was blind to the tenuous future of the Crusaders. She asked the pope to promote a Second Crusade to fortify the Christian presence in the Levant.

While giving a facelift to Jerusalem, Melisende faced a new crisis: her son declared that since he was of age, he should become sole ruler. Melisende maintained Baldwin was not ready to govern. The disagreement resulted in a brief civil war which Baldwin won. But within weeks they made peace and Melisende became Baldwin’s adviser.

In 1161, Melisende suffered a stroke. Her sisters nursed her but she died that year at the age of 56. She was buried at the Holy Virgin Church close to her mother.

Forty years earlier Melisende’s farsighted father had been spot on in trusting that his teenage daughter had the strength of character to make a great queen. After all, in Old German Melisende means “strength and work.”

Zabel Yessayan

By Jennifer Manoukian

“The very first time I read a book in French and understood almost everything I read, I could sense that new horizons were opening up in front of me.” 1

As she was writing her memoir The Gardens of Silihdar in the early 1930s, Zabel Yessayan recalled this hopeful moment forty years earlier, which would not only come to define her literary career, but also mark the beginning of an affectionate relationship with French culture that would last until the very end of her life.

This relationship was forged a world away from France, in late-nineteenth-century Constantinople. Born into a middle-class family in 1878, young Zabel—like many other Armenians of her class and generation—spent her childhood reciting the fables of Jean de la Fontaine and devouring the works of Balzac and Baudelaire. Once she set her sights on becoming a writer, studying in France was a natural choice. In 1895, seventeen-year-old Zabel set out for Paris on her own and settled into student life in the Latin Quarter, studying literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne, while working as an editorial assistant for the Nouveau dictionnaire illustré français-arménien (1900) to support herself.

It did not take long for her to start writing in Paris, adopting contemporary French literary styles, models and forms in her works in both Armenian and French. By experimenting with these French literary currents and translating inventive French writers into Armenian, Yessayan played a major role in introducing the Armenian reading public to new forms of literature, firmly positioning herself at the forefront of the Armenian literary communities of Paris and Constantinople in the early twentieth century.

But it was not solely for Armenians that Yessayan wrote. Within five years of her arrival in France, she had contributed to respected French literary publications, including L’Humanité nouvelle and Écrits pour l’art. In these journals, Yessayan acted as a kind of intermediary between two literary traditions by striving to acquaint a general French readership with contemporary Armenian literature. Through her translations of Armenian literary giants, reviews of recently published Armenian books and her own original writings in French, Yessayan shined a spotlight on Armenian literature and culture at a time when news of massacre and oppression dominated the French public’s general impression of Armenians.

Yessayan returned to Constantinople in 1902, but would move back to France in the aftermath of World War II. Summoned from the Caucasus where she had been recording the accounts of genocide survivors and translating them into French, she once again served as an intermediary between the French and Armenian peoples upon her return to Paris in 1918. This time, she was tasked by the Armenian National Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference with conveying the particular experiences of Armenian women during the war in a way that would resonate with the French public she knew so well.

Yessayan spent the majority of the 1920s living on the outskirts of Paris, during which time her politics changed dramatically. Disillusioned with life in diaspora, she became a staunch defender of Soviet Armenia and ultimately settled there permanently in 1933.

Though she left France behind, Yessayan’s admiration for French culture remained unwavering. Before her arrest and mysterious death in the early 1940s, she taught French literature at Yerevan State University and was known for instilling in her students a reverence for the culture that nurtured her literary aspirations as a young writer. “All of us without exception were under the influence of Zabel Yessayan,” wrote noted academic Ruben Zaryan, one of her students at the time, “and we all thought that French literature, particularly French prose, was the best in the world.”2

1Translated by Jennifer Manoukian in Zabel Yessayan, The Gardens of Silihdar. Boston: AIWA Press, 2014, p. 131.

2 Translated by Ara Baliozian in Zabel Yessayan, The Gardens of Silihdar & Other Writings. New York: Ashod Press, 1982, p. 20

Mélinée Manouchian

By Rene Dzagoyan

Wife of the French Resistance hero Missak Manouchian and an active member of the resistance group that her husband formed to fight against the Nazi occupation, Mélinée Manouchian remains in French historical memory as a symbol of the struggle of women for freedom. Her memory was immortalized in a poem written by poet Louis Aragon, which is still recited in schools today, and put to music by composer Léo Ferré.

Like many Armenians of her generation, Mélinée (née Soukémian), born in 1912, was an orphan survivor of the Armenian Genocide. Her father, a senior official at the postal service in Constan-tinople, disappeared with her mother during the deportations in 1915. Mélinée was three years old at the time.

Taken in by a Protestant orphanage, she and her sister Armène were housed for a time in an orphanage in Smyrna, but were sent to Salonica in Greece after the city was burned by Turkish nationalists. From there, she was placed in various Armenian families in Corinth. Mélinée was thirteen years old when, in 1926, she and her sister arrived in Marseille, France. After living in the Tebrotzassère orphanage and school established by the Association of Armenian Women Friends Tebrotzassère (ADAAET). It was there that Melinee was introduced to the Armenian language and heritage. Three years later she was sent to an Armenian high school founded by the French Armenian community. where she was taught stenography. It was a skill that would serve her well during the Resistance.

Mélinée was twenty-two years old when she met Missak Manouchian for the first time. A carpenter by trade, he was working in Citroën automobile factories at the time. She enjoyed talking about the day Missak proposed to her. When Missak had invited her to a café in Paris, she asked him if he had a girlfriend or if he was in love with a woman. Missak said that he had, in fact, been in love for quite a while. Mélinée asked if he had a picture of this young woman, and Missak said yes. When Mélinée asked him to show it to her, Missak took a small object out of his pocket and handed it to her. It was a mirror. They married in 1934.

That same year, the couple joined the Armenian Relief Committee (Hayasdani Oknoutyan Gomidé). Missak and Mélinée quickly assumed leadership positions in the committee, all while becoming members of the French Communist Party. As soon as the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact was signed between Hitler and Stalin in 1939, French laws against Communist immigrants were strengthened. The fact that Missak and Mélinée belonged to Communist organizations led to a long series of imprisonments and separations, which forced them to operate in secrecy until 1943. It was in the same year that a group of Communist Resistance fighters, the Francs-tireurs et partisans—main d’oeuvre immigrée (FTP-MOI), formed and was led by Missak Manouchian.

In this group of underground resistance fighters, Mélinée’s role was to draft leaflets, transmit messages and transport weapons. On November 16, 1943, Missak was arrested by the Gestapo. Mélinée, who was also wanted by the Nazis and sentenced to death, hid in the Aznavourian’s home, all while continuing to act as a liaison between various resistance groups. On February 21, 1944, Missak was executed by the Germans atop Mount Valérien on the outskirts of Paris. After his death, Mélinée continued his struggle until Nazi Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945.

Once the war ended, Mélinée became the secretary of the Jeunesse Arménienne de France (French Armenian Youth Organization), which was sympathetic to Soviet Armenia. It was during this time that she published the poems that Missak had written all throughout his life.

In 1947, along with 300,000 other Armenians in France, she left for Soviet Armenia, where she worked as a secretary for the Institute of Literature at the Armenian Academy of Sciences. Deception quickly drove her to long to return to France, but she had to wait seventeen years before she could see Paris again in 1963.

By the time she returned, Louis Aragon had already made her famous with his 1955 poem “Strophes pour se souvenir” (Stanzas to remember), which makes use of Missak’s words in his final letter to Mélinée. Four years later, in 1959, the poet and singer Léo Ferré turned the poem into a song, “L’Affiche Rouge” (Red Poster). From 1959 until the election of President François Mitterrand in 1981, French authorities banned the song from radio and television.

In 1984, Mélinée testified in support of four Armenian militants involved in Operation Van, who took over the Turkish Consulate on Boulevard Haussmann in Paris. In court, she addressed the presiding judge with a phrase that would become famous: “These are my children, the children I never had with Missak.”

After a lifetime of keeping one step ahead of danger and controversy, Melinee, now living only on a war widow’s pension, had finally found a place to call home in Antony, a southern suburb of Paris where the mayor was Patrick Devedjian, one of the militant’s attorneys. In 1989, surrounded by the leadership of France’s new ruling party, Melinee was able to attend the unveiling of a monument in honor of the Manouchian Group. This would be last time she would make a public appearance. She died that same year, at the age of 76.

Translated from French by Jennifer Manoukian

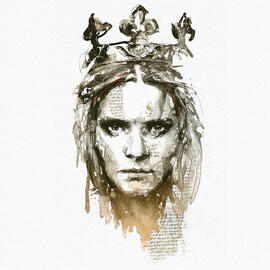

Banner illustrations by Florian Nicolle