In south-western Netherlands, in the town of Terneuzen, the first thing the teenagers learn at school about World War I is not the assassination of the Austrian Archduke and the chain of events following it that caused the war. It’s the Armenian Genocide atrociously committed by the Ottoman Empire. While Dutch textbooks never reflect on this, their teacher of purely Dutch origin ensures that his generation of students knows the truth after finishing school.

Dirk Roodzant’s first encounter with Armenians in his student years was fateful in expanding his horizons and career path. Immersing himself in Armenian culture and history, he devoted over 30 years of his life to studying the Armenian Genocide and raising his non-Armenian voice to unveil the truth.

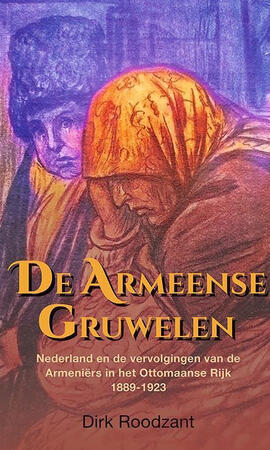

Upon the publication of his book The Armenian Horror, we spoke to Roodzant about his long journey its challenges, and the important findings of the study.

Q Dirk, thanks for agreeing to give an interview. Tell us about your first encounter with Armenians.

A It was the year 1985. My friend and I were undergraduate students at university when we decided to take up something new and go to a summer camp abroad. Soon, of a few options we applied, I received a call with an extremely poor connection. The only clear connection between us was, “Would you like to come to our camp?” and I said, “yes.” In between, I could catch some cut-out words, too, such as Amish.

Therefore, I was pretty sure I was accepted to an Amish camp, and at the airport, my eyes were looking for someone with light hair and greenish eyes [he laughs] holding a welcoming sign with my name. Instead, I found my name in the hands of a black-haired, bearded man of middle height, and only on my way to camp did I realize I had misheard the information.

The months following it were simply amazing. I served as a counselor at AGBU Camp Nubar in the Catskill Mountains of New York State and was so fascinated by the quality and organization of the Camp, as well as the warmth of the environment that I made sure I came back for a summer service the following six years. That’s where I first learned about Armenians, their fantastic dances, songs, cuisine, culture and history.

Q How did you first learn about the Armenian Genocide? Was it at university?

A Unfortunately, in my university years, I never came across chapters about the Armenian Genocide, and, you know, back then, the resources mainly were in hard copies with a lack of easy access to information beyond the curriculum.

So, the first time I learned about the Armenian Genocide was at Camp Nubar. People there spotted my interest in everything Armenian and started nurturing it with anything at hand. They presented books, shared family stories, and invited me to dinners with Armenian delicacies.

During one such dinner, an old Armenian woman, a Genocide survivor, happened to tell me what hardships she and her family had to endure while fleeing from Ottoman Armenia to the Syrian desert. She opened my eyes with her story. As a historian, I realized that even I didn’t know what had happened, and I made up my mind to become one of those non-Armenian voices to uncover the truth to the world.

Q Let’s go deeper into the study. What resources did you use? How challenging was your journey, and what’s the novelty of your book?

A Those years, it was complicated enough to talk about the Genocide. The research was poor, the Turks were pursuing a denial policy, and much more. But I made myself familiar with whatever was accessible in the Dutch archives. Later, in 2012, I received a € 100,000 grant from the Dutch government to extend my study in foreign archives.

Over the course of ten years, I collected countless pieces of evidence by visiting several archives in Germany and Britain, including the British National Archives, the Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office of Germany, and the Lepsiushaus. Yet, I had to select the focus of the book and wound up with a topic never explored before–the Netherlands’ response to the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

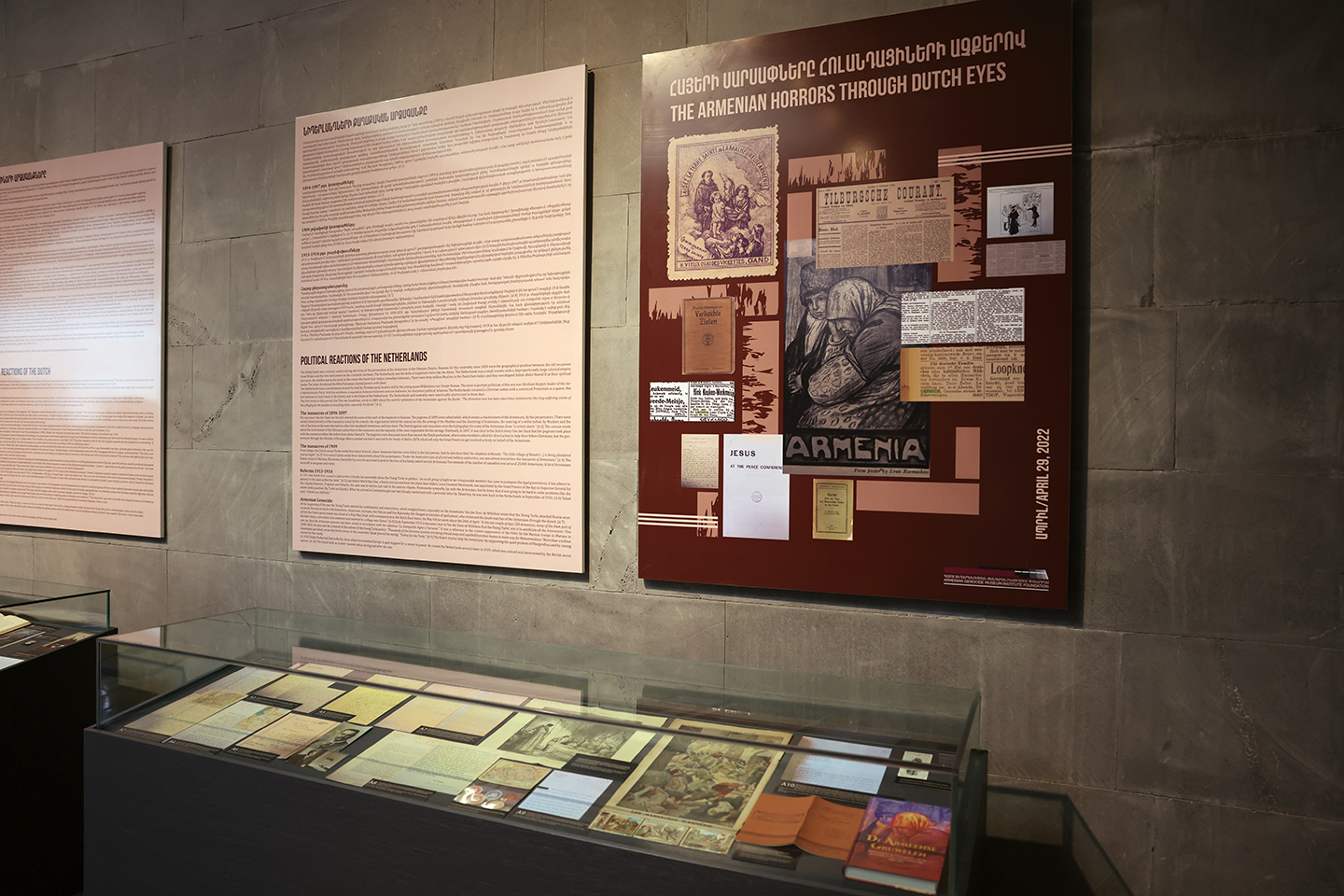

In effect, the Netherlands was one of the few countries that maintained neutrality during WWI. It stymied the state to officially respond to the crisis or issue a statement. Yet, the newspapers in Holland covered the massacres. What’s more, the Dutch politicians, envoys, consuls, missionaries, ordinary tourists, writers, artists, and even engineers appear to have reported on the “Armenian horrors happening in the Ottoman Empire.” Mass media agents created postcards to raise awareness of the atrocities. On a humanitarian level, the Dutch people even organized a fundraiser to support Ottoman Armenians.

With the book, I wanted to shed light on all those facts that have never been touched upon for the new generation to acknowledge and condemn over century-old unlawful activities and ensure that it happens never again.

Q You know that the Lachin Corridor, the only road for Artsakh to the outside world, is blockaded by Azerbaijan. What are your thoughts on this?

A A good question, because I do have an opinion on this matter. I am currently working on an article titled “The Road to Genocide,” which already speaks for itself. After so many years, Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, continues the Geno-cide policy against the Armenian people. The blockade is nothing but a tool to serve this purpose.

As the UN Genocide Convention states: “Genocide means any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (C) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

By cutting the gas and electricity off and suspending access to vital supplies, including food and medicine, Azerbaijan violates the fundamental human rights of the Artsakh people, yet remains unpunished, as did Turkey in the 20th century. At some point, the world has to recognize the unlawfulness of these states and raise a firm voice to stop the Turkish-Azeri evil hand.