At the turn of the 20th century, world events began to mark a major shift in the cultural and socio-political landscape that would reverberate across the globe for the next hundred years.

During this period, as the drum beat of existential threats to the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire was growing louder, a new musical sound was gaining strength in the United States.

It was rooted in centuries of slavery, wherein Africans sold into bondage began blending their musical traditions with that of their masters. Singing call-and-response style songs while working the cotton fields, they would fuse Western church music harmonies and melodies with their African rhythms. Their makeshift instruments included washboards, jugs, and an array of other everyday objects.

Within a matter of decades, a new musical idiom called the blues had been created out of a necessity to express the angst and hope of an oppressed people. In the years after slavery was abolished, the blues made its way into bars, clubs, and brothels, where musicians were able to develop what would soon be known as jazz.

In 1915, famed New Orleans pianist Jelly Roll Morton’s composition “Jelly Roll Blues” was the very first jazz arrangement to be published, giving a new artform the opportunity to expand its reach. By the early 1920’s, this new sound marked what is known as the Jazz Age.

Yet, with prohibition in place in the U.S., illicit clubs known as speakeasies were the places where people could consume alcohol and dance to music. As a result, jazz became associated with immorality, a reputation that permeated the mainstream mentality for years to come.

By this time, the short-lived independent First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920) had come and gone, and Soviet rule spread across the region. Although this provided stability, Armenians were forced to adhere to the suffocating Stalin regime, which meant any Western influence was deemed to be immoral. And what could be more representative of Western immorality than one of America’s original artforms.

By the end of World War II, attitudes changed toward the West and it was undeniable that jazz had gained great popularity, heralded by the big bands of Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and countless others. The government decided that this portion of American culture could be used for ‘export’ to promote its post-war ideals of democracy, and soon state sanctioned tours of jazz bands alongside U.S. troops through war torn Europe were commonplace. Jazz had arrived in the old continent reaching ever closer to the tiny Soviet Republic of Armenia.

Suffice it to say, countries within the USSR were not included in these tours, and Armenians learned about and consumed jazz as many under Soviet rule did with American cultural exports: through a heavy filter and in the shadows.

“I would put our family radio under my pillow and catch Willis Conover’s ‘Voice of America Jazz Hour’, listen to Duke Ellington, Count Basie” says pianist Vahagn Hayrapetyan, one of Armenia’s leading jazz champions and performers, “but my grandmother would find me and say ‘Hide that radio! They’ll come, the KGB will come and take you!’”

The Avakian-Motian Effect

This does not mean that Armenians did not have a hand in moving this still developing artform forward; two key figures on opposite sides of the music industry appear in the history of jazz at this time: producer George Avakian and drummer Paul Motian.

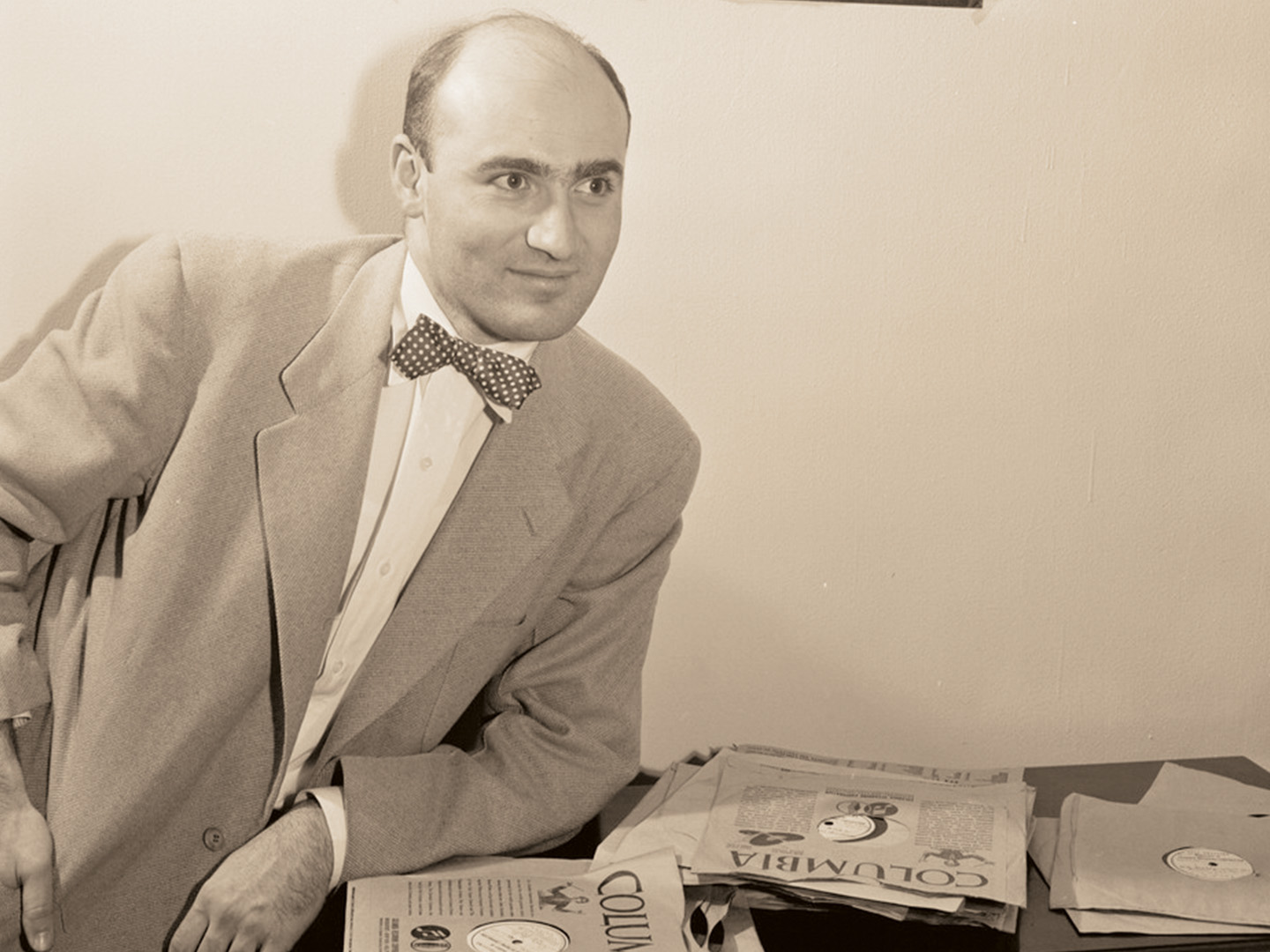

Born in Russia in 1919, Avakian moved to New York with his family at the age of four, and quickly fell in love with jazz. He was hired by Decca Records while still in college, going on to produce Chicago Jazz in 1940, considered to be the first ‘jazz album’ of completely original recordings. Not long after, he was hired by Columbia Records, where he produced a series of albums of previously unreleased Louis Armstrong recordings and worked directly with artists such as Frank Sinatra and Doris Day.

Avakian was also a prolific writer on the subject of jazz, being published in Down Beat and Jazz Magazine, and in 1948 began teaching one of thefirst jazz history courses at New York University. Throughout his career, Avakian worked directly with some of the most influential artists of the 20th century, including Ravi Shankar, Gil Evans, Art Blakey, Tony Bennett, and was even responsible for signing two major artists to Columbia Records who would go on to change the course of music: Dave Brubeck and Miles Davis. Moreover, he served as Recording Academy (Grammys) Chair, making it safe to say that the musical landscape of the last 70 years would not have been the same without Avakian.

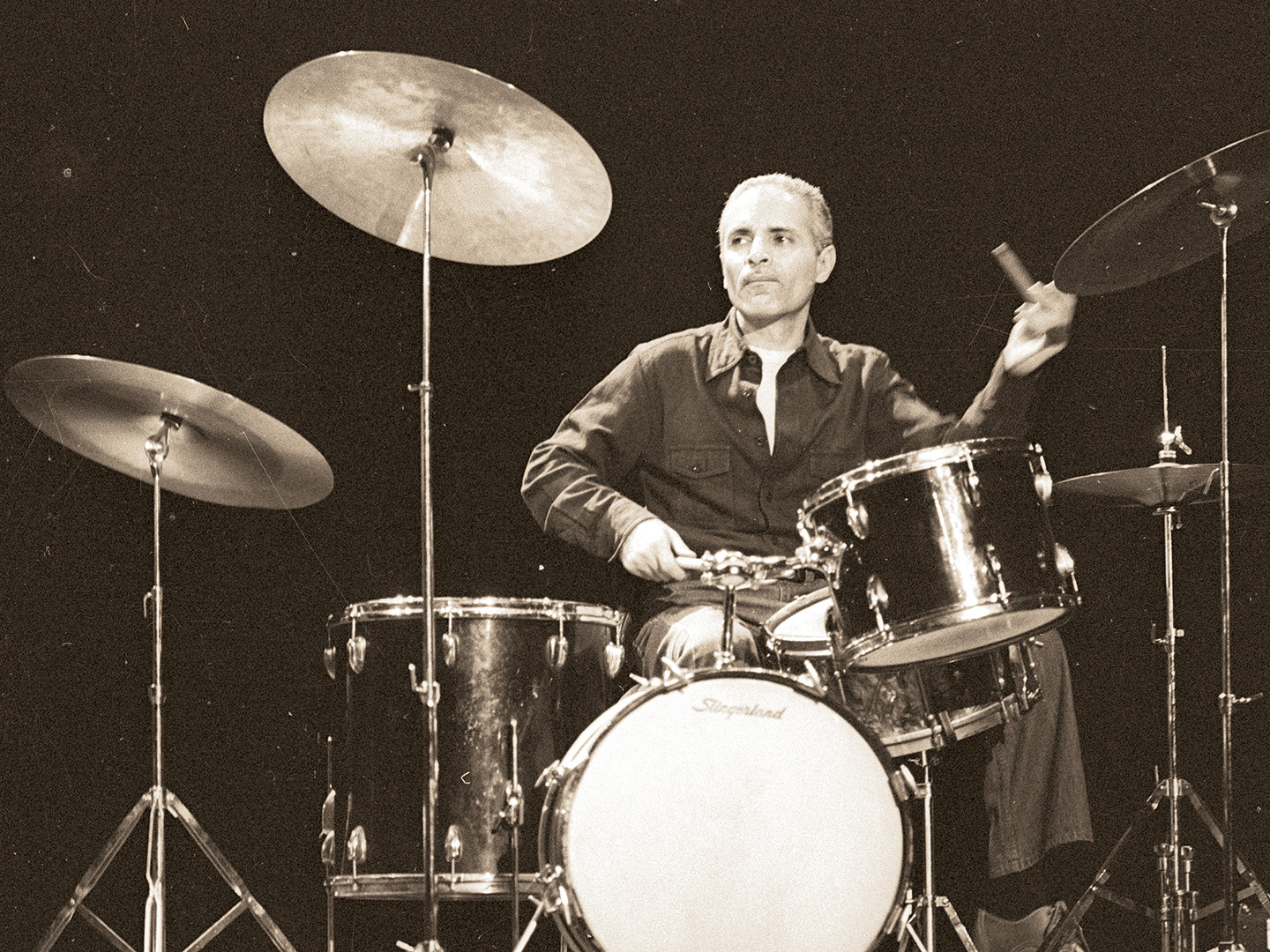

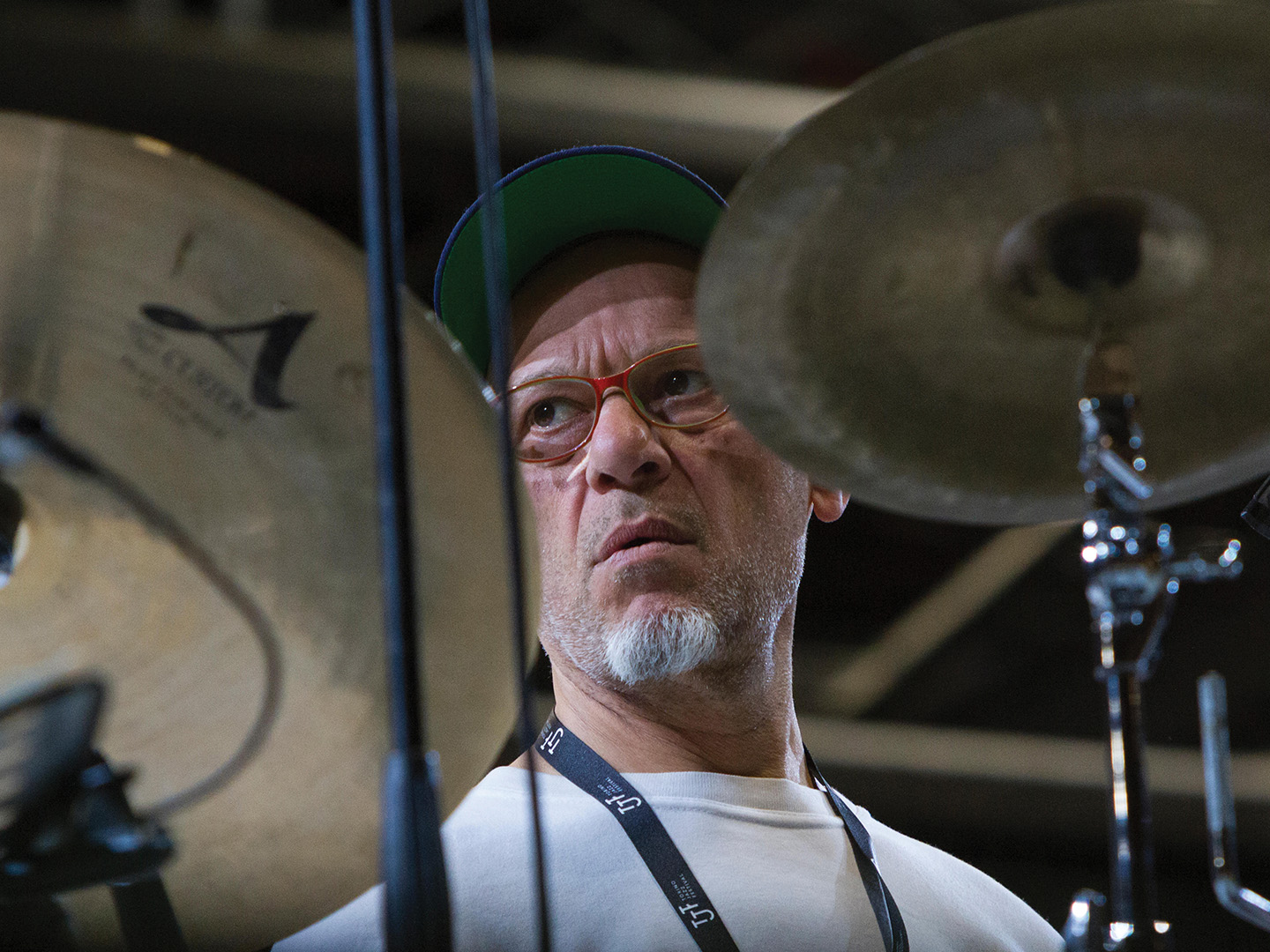

On the other side of the industry was the master drummer Paul Motian. A native of Philadelphia, Motian was already touring in his teens, and after a short stint with legendary pianist Thelonious Monk in the mid 50s, joined pianist Bill Evans. There was a shift happening in jazz towards the middle of the century, not just from swing towards the more aggressive bebop being forged by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, but also towards a more experimental and freer music.

It seems that both jazz and Motian benefited from their coming together at this point in time. As pianist Ethan Iverson succinctly put it, “Many drummers care about tradition and heritage. Motian also had an abiding interest in experimentation, dating perhaps to a rehearsal with modernist composer Edgar Varèse in the mid 50s. When jazz broke open in the early 60s, it was perfect for Motian, who would go on to be the greatest free tempo drummer of the older generation.” As Iverson also notes, this freedom allowed him to do certain things such as detune his drum set in a salute to his Armenian heritage, which can be heard in the legendary Village Vanguard recordings with the Bill Evans Trio from the early 60s.

Motian continued to delve into this new branch of jazz, carving out a path for generations to come. He began releasing music as a bandleader in the 70s with ECM Records and through his recordings with guitarist Bill Frisell and tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, which remain some of the most instrumental in free jazz, Motian began to shine as a composer, presenting simple yet beautiful melodies reminiscent of Armenian folk songs.

Check out Michael Sarian’s companion playlist for this article

Making Sound Waves in Armenia

While Avakian and Motian were influencing the development of this 20th century artform, musicians in Armenia were learning about a new type of music being filtered down through a Soviet lens. If musicians wanted to perform this new Western type of music, they either had to incorporate Soviet themes (which, in turn, created a new version of the music), or play it in a satirical context or theatrical setting, so as to ridicule these new American ideologies of freedom and democracy.

In the late ‘40s, ‘jazz’ was erased from the State lexicon and all orchestras performing this new music were dissolved… all except for the Armenian State Jazz Orchestra, an ensemble created in 1938 by composer Artemi Ayvazyan, and still performing to this day under the direction of saxophonist Armen Hyusnuts. So, much like it had been in the U.S. decades ago, jazz became an underground musical genre in Soviet Armenia.

“In order to perform and ‘conceal’ jazz, musicians translated the names of the jazz standards into the local language and added elements of local folk music into their performances,” says Rima Tigranyan, lecturer on the History of Jazz in Armenia, “in turn beginning the creation of a new music.”

In order to perform and ‘conceal’ jazz, musicians translated the names of the Jazz Standards into the local language and added elements of local folk music into their performances.

It wasn’t until the 70s, when jazz was no longer considered ‘dangerous’, that the genre broke through the Iron Curtain. The Armenian State Jazz Orchestra was able to tour and perform Armenian jazz across the globe, including in the U.S., quickly becoming one of the most popular jazz ensembles of the region. Many of today’s venerated figures in the Armenian jazz community were being exposed to this music, learning from some of those who had helped keep the music alive throughout Soviet rule. Figures such as pianist and conductor Konstantin Orbelyan and drummer Armen “Chico” Tutunjyan dedicated their lives to moving the music forward and educating the next generation of musicians.

But still, recordings of the jazz greats that George Avakian was producing in the U.S.—such as Miles Davis—weren’t readily available. Hayrapetyan explains that the lack of resources just made their hunger for discovery even greater, “When I was growing up, in the 70s and 80s, I’d fly from Yerevan to Moscow just to buy an LP. And that one LP was like gold. We’d listen to that, analyze it, learn it upside and down, because that’s the only source we had.” One way or another, Armenia’s next generation of jazz musicians and educators were finding ways to learn about this new music of possibilities, which would undoubtably make its mark on a new Armenia.

When I was growing up, in the 70s and 80s, I’d fly from Yerevan to Moscow just to buy an LP. And that one LP was like gold.

Post-Soviet Progressions

By the time Armenia gained its independence in 1991, jazz had become a symbol of freedom across the country, and dozens of new jazz clubs and ensembles were appearing throughout Yerevan. Important figures in this new chapter in the history of Armenian jazz begin to establish themselves; chief among them, the Grammy Award winning multi-instrumentalist Arto Tunçboyacıyan. Born in Istanbul, Tunçboyacıyan relocated to Yerevan in the late 90s after nearly two decades in New York City, and quickly connected with other musicians eager to explore new opportunities. Alongside Hayrapetyan, who had also lived, studied, and worked in the U.S., Tunçboyacıyan would go on to form the Armenian Navy Band, one of the country’s most influential jazz groups. They recorded five albums, toured the world, and introduced Armenian culture to new audiences as they combined Armenian traditional music and instruments with jazz.

Before the Armenian Navy Band, however, singer Datevik Hovanesian had been making her mark on the music scene in Armenia and Europe. A native of Yerevan, one of her first performances was on the Armenian National Radio at the age of eleven, and by the time she was 20, was touring internationally with the Armenian State Jazz Orchestra in the mid 70s.

Whereas the group led by Tunçboyacıyan described themselves as ‘Avant-Garde Folk Music’, Datevik, popularly known as ‘The First Lady of Jazz of the Soviet Union’, was touring the world performing a more traditional form of jazz, but among the standard repertoire she included jazz arrangements of traditional Armenian music in her setlists. She recorded and released six albums, not to mention over 100 singles, taking her own brand of Armenian Jazz all over the world, before finally relocating to New York City in the early 90s. Tunçboyacıyan’s Armenian Navy Band and Datevik were driving forces in moving Armenian Jazz across borders and defining a new branch in the genre: ethno-jazz.

Institutionalizing a Genre

As more people were increasingly drawn to jazz in the 90s, Armenia’s cultural and educational institutions responded: the Yerevan State Conservatory now offers a jazz curriculum, and the Yerevan Jazz Festival has welcomed some of the genre’s brightest stars to perform in Armenia, such as pianist Herbie Hancock, singer Dee Dee Bridgewater, trumpeter Arturo Sandoval, and countless others.

A native of New York, pianist Armen Donelian first traveled to Yerevan to perform at the inaugural Yerevan Jazz Festival with Datevik Hovanesian in 1998. Having extensive experience in education (he has been on the jazz faculty at The New School in New York City since 1986), Donelian decided to stay for a few weeks, offering a workshop on jazz piano and ear training at the Yerevan State Conservatory.

Donelian found that Yerevan was indeed fertile ground for jazz education, “It became clear that the students were eager and interested in learning more about jazz. So, the following year, I organized a visit on my own and stayed for a month, teaching at the conservatory alongside some faculty there, including Armen Hyusnuts. There were professors at the conservatory who had been involved with jazz for decades before I ever arrived, so it was a learning experience for me as well—an exchange of ideas.”

The next year, in 2000, Donelian returned to Yerevan as a Fulbright Senior Scholar and spent an entire semester teaching at the conservatory. He would go back several times throughout the years to teach and perform, “I noticed a steady progression since the first time I went in 98. The teaching that we had been doing, not just myself but great local musicians such as Armen and Vahagn, was starting to bear fruit. This is the natural progression of life. I felt that the seeds had been planted, and the tree had begun to grow.”

With momentum in its favor, the jazz scene has changed drastically since the early 90s. “When I was growing up, there weren’t that many jazz musicians,” says Hayrapetyan. “There were many good musicians, but not that many jazz musicians. We didn’t have any trombone players or sax players, and we only had one trumpet player, Yervand Margaryan, but of course he was always busy.” Now things have changed, and the local jazz scene is bursting with talented young musicians.

The Regional Jazz Hub

As more and more musicians were drawn towards jazz, so grew opportunities for them to showcase their talents. “There was a demand for the club,” explains pianist Levon Malkhasyan, who opened his jazz club ‘Malkhas’ in 2006. “We’ve had a full house since the first day and never stopped.”

Levon, who had been organizing a number of jazz festivals leading up to that first Yerevan Jazz Festival in 1998, says that not only has the opening of jazz clubs provided opportunities for the development of local talent (he sees new faces on the bandstand every night), but jazz has also turned Yerevan into a jazz hub for the region. “We have a lot of tourists at the club, from all the former Soviet states and abroad. Just yesterday, I was asked to open the club a bit earlier than usual and play since we had two big groups of tourists come in. The place isn’t that big, so when you have both tourists and locals come in, it’s pretty packed.”

Lingering Questions

For as much popularity the genre has gained in the past few decades, the persistent question among fans and critics—for which musicians are hard-pressed to answer‚ is “what exactly is Armenian Jazz?” Over the past thirty years, it would be difficult to find a jazz musician of Armenian descent who hasn’t performed or recorded at least one arrangement of a Komitas piece, and for better or for worse, that was considered ‘Armenian Jazz’ for some time in the mainstream. In recent years, however, an increasing number of musicians have been following in the steps of the Armenian Navy Band and influencing jazz with Armenian rhythms, modes, and melodies, as opposed to jazz influencing a rendition of an already existing Armenian composition.

Going Global

Pianist and Gyumri native Tigran Hamasyan has been a leading force in the global jazz community for nearly two decades. He has released over ten albums as a leader since winning first prize in the highly coveted Thelonious Monk Jazz Piano Competition, garnering praise from respected publications and musicians alike. Through his success, Hamasyan has made Armenian rhythms, modes, and melodies a staple of modern jazz music.

“One of the most compelling aspects of Tigran’s music is the tenderness he has towards his roots,” explains Christiane Karam, vocalist and professor at the Berklee College of Music. “Tigran is subtle about the musical elements that he lets seep in from the folk tradition, and yet they land and connect in the most poignant way. His sound is absolutely unique.”

Like most jazz musicians of his generation, Hamasyan first honed his craft by studying privately, in his case (and countless others) with Hayrapetyan himself. He even attended Donelian’s very first masterclass in 1998 when he was eleven. In the years since, he has arguably helped pave the way for a new generation of Armenian jazz musicians, such as singer and tar-player Miqayel Voskanyan. While still residing in Yerevan, Voskanyan has been touring the world with his band, performing their own brand of ethno-jazz, which many call ‘Modern Armenian Folk Music’. Whether arrangements of traditional pieces or original compositions, Voskanyan’s singing in Armenian and tar playing are at the forefront of the ensemble, and are far from a gimmick.

Tigran is subtle about the musical elements that he lets seep in from the folk tradition, and yet they land and connect in the most poignant way. His sound is absolutely unique.

By Any Other Name

Whatever you want to call it, ‘Armenian Jazz’, ‘Ethno-Jazz’, ‘Avante-Garde Folk Music’ or ‘Modern Armenian Folk Music’, it is undeniable that after decades of finding its way into Armenian ears, this 20th century American artform is now being elevated thanks to centuries’ old Armenian traditions. Through the music of Hamasyan, Voskanyan and countless others, generations of musicians to come will have been influenced (perhaps unknowingly) by the music of Komitas, Sayat Nova, Babajanyan, and soon enough we’ll be hearing ‘Armenian Jazz’ performed by musicians of all backgrounds across the globe.

With files from Gevorg Mnatsakanyan