The story of the Armenians in Lebanon runs parallel to the very history of the state of Lebanon. Both start in the early 1920s, undergo the shaping process in the next decades, grow and develop in the 1950s, face crises during the Cold War, and reach their peak between 1960 and 1975. Furthermore, both suffer extensively during the war years, and both are inspired with hopes of revival with the Taef Accord of 1989. These materialize to a certain extent until 2005. With the assassination of PM Rafic Hariri, both Lebanon and the community are forced into a tunnel, well aware of the necessity of coming out of it as early as possible.

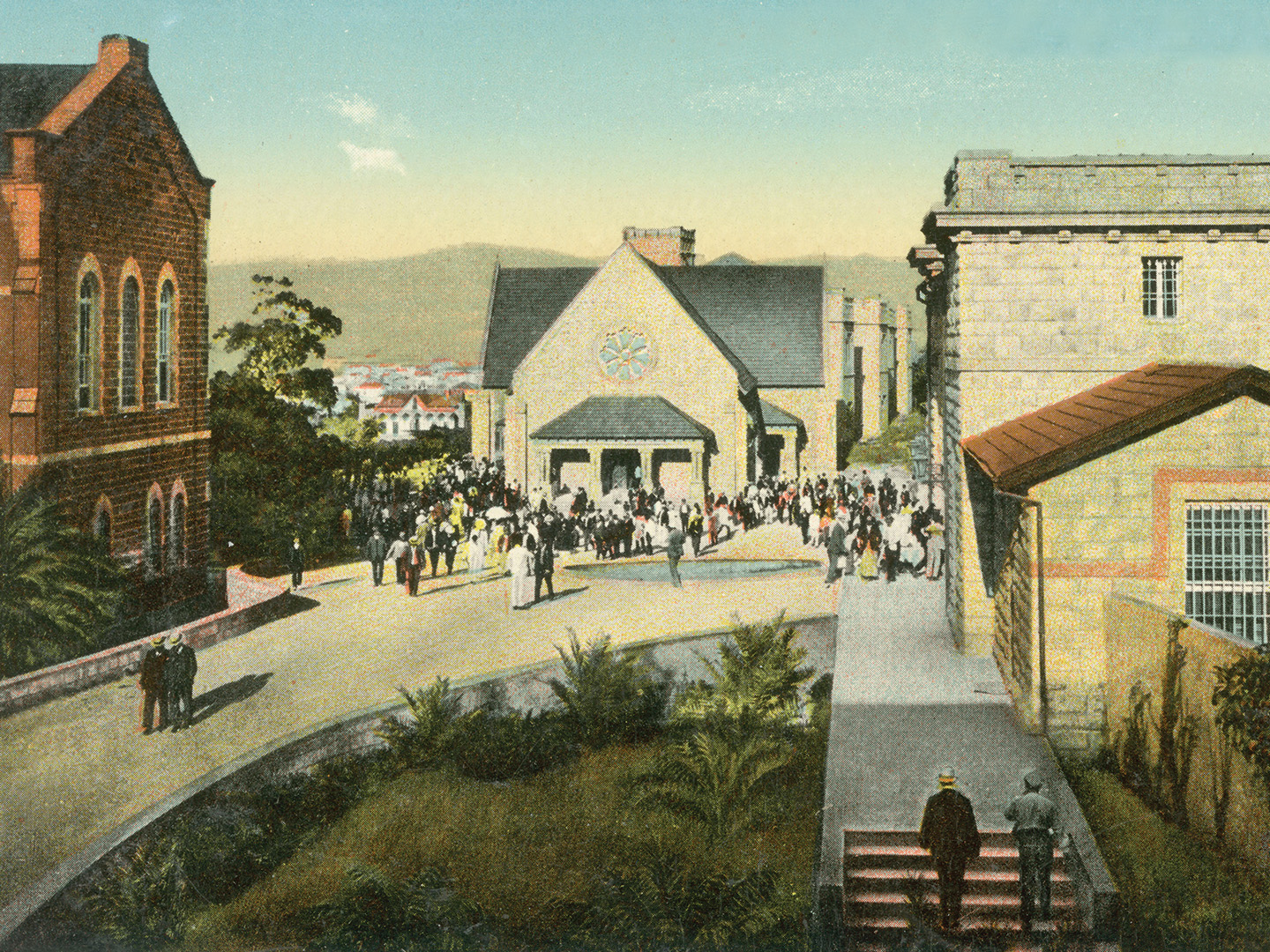

During WWI most of the local Armenians—some 1,500 in total—lived in Beirut. These were carpet dealers, photographers, businessmen or agents of Armenian business companies, etc. A few families lived in Saida, a small community of Protestant Armenians and students was isolated in the Syrian Protestant College (SPC, later renamed AUB), while a number of clerics and lay Armenians lived in the surrounding villages of the Catholic Armenian monastery of Bzemmar (built in 1748). All, however, maintained a low profile and were under strict Ottoman surveillance. Last but not least, some 1,000 Armenian orphans were being turkified in the notorious Aintoura orphanage under the supervision of Halide Edib.

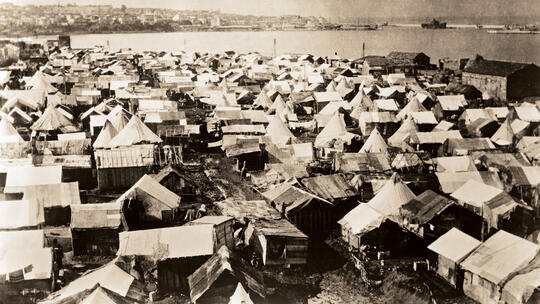

On October 20, 1921 France signed the Ankara Agreement and compromised its wartime pledges concerning statehood in Cilician Armenia. Terrified of an imminent genocide, Armenians were forced to take refuge in Lebanon and the neighboring countries. As of November 1921, the French disembarked the Armen-ians all over coastal Greater Lebanon, which was proclaimed a year before, in September 1920.

Copying a modified version of the Ottoman millet system, Lebanon was to become a federation of communities, where power was shared by and allocated to the communities according to their demographic weight. Fixing a share to the communities diverted the centuries-old intercommunal conflicts into intracommunal and reduced the chances of country-wide flare ups. The Lebanese consociational system granted cultural autonomy to the communities, guaranteed them a large degree of freedom and liberty, and produced a democratic system and a market economy unprecedented in the region. However, it compromised Lebanon’s sovereignty and caused the formation of a weak state, which, in turn, made the Lebanese self-reliant rather than state-dependent. Indeed, the weakness of the state trained and ‘educated’ the Lebanese to rely on themselves, develop and strengthen their social skills to adapt, reformat themselves and integrate to the milieu they are put in with less difficulty than the citizens of Syria and Soviet-styled states, for instance.

Naturally, the incoming refugees were to be accommodated into the system, which fostered their gradual transformation into a coherent and well-organized community. The Lausanne Treaty granted citizenship and entitled them voting rights in the first elections of the Lebanese House of Representatives in 1925 and have their MP in 1929. Soon after they were represented in the municipal council of Beirut. The number of Orthodox Armenian MPs increased to two in 1943 and to three in 1951. Between 1960 and 1992, the community was represented by four MPs and after the Taef Agreement their number was further increased to five. The Catholic Armenian and the Protestant communities are each represented by one MP as of 1951.

The decade witnessed a process of housing improvements. The tents were transformed into tin shelters and wooden shacks, and as of the late 1920s-early 1930s the refugees gradually moved to nearby betonvilles they constructed in Mar Mekhayel, Nor Hadjin, Bourdj Hamoud, Hayashen and other areas. The easy access to the centreville labor market enabled the refugees to take steps towards socio-economic advancement. Health and hygiene improved as of the late 1940s and infant mortality rates fell significantly.

Unlike the communities of Syria and Egypt, the pre-1920 Beirut community lacked the organizational infrastructure to address the needs of the incoming refugees. Gradually and in various proportions the Church, AGBU, NAASR, AMAA, various compatriotic unions, the Near East Relief Society, the Jesuits’ order and the political parties took charge of devising a communal system to manage the refugee affairs. Up to the late 1940s the community was busy constructing its residential areas and community outlets including schools, churches, launching organizations, creating its cultural space and shaping its identity.

The settlement of some 12,000 Armenians of Musa Dagh and the Sandjak of Alexandretta in Lebanon in 1939, and the repatriation of some 20,000 Armenians to Soviet Armenia in 1946-47 marked the phase of relative demographic stability and economic abundance as the once orphan craftsmen satisfied local market demands during WWII and after.

With the proclamation of independence in 1943, Lebanon set foot into the era of western-styled politics and economy. The country was perceived as the most democratic state with an almost laissez faire economy, which attracted the upperclass of the region, looking for security, stability and potential economic opportunities.

In the 1950s, the community could not bypass the Cold War and was challenged by the church crisis of 1956 and the fratricide of 1958. Ironically, this was the time when the community youth had a larger access to higher education, as Armenian high schools rivalled the best local private and public high schools and enabled the Armenian students to achieve great results. Armenian students constituted around one-third of the AUB Lebanese student population. This was due to Diaspora Armenian philan-thropic organizations like the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, the AGBU, etc. that granted hundreds of scholarships per year. The launching of Haigazian College in 1955 (currently Haigazian University) marked the community’s highest institutional achievement in education in the Armenian Diaspora. Haigazian became the flashpoint for compromises among the younger generation.

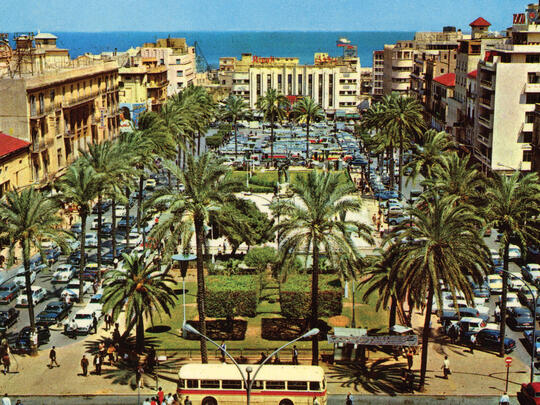

As of the early 1960s Lebanon became the Switzerland of the Middle East, while Beirut—the most densely populated Armenian community in the Diaspora—became its Armenian capital and its nerve center. It embraced the religious headquarters of both the Armenian denominational churches and conventional parties. Its unsurpassed nationalist vigor networked and initiated the formation of the Diaspora transnation. Indeed, cultural autonomy had enabled the intra-communal integration and the gradual generation of a prosperous, affluent culture with a unique Lebanese Armenian identity that influenced the shaping of varigated Diaspora Armenian community identities. On the local scene, a large portion of the Armenian community belatedly embraced the practice of the Arabic official language as the community started to take measures and steps to claim full share in the state system. The Lebanese war, however, disrupted it.

On the eve of the 1975 Lebanese war the over-200,000-strong community (it had grown from a mere 32,000 in 1932 to some 55,000 in the early 1950s and quadrupled thanks to both natural growth and continuous inflows from neighboring countries, constituting some 6-7% of the total population) was the largest Christian community in Beirut (four of the five Armenian MPs were elected from the Beirut constituencies), had 25% of the Lebanese bank savings and a significant share in the marketplace which made it the economic tiger of the country. One need to underline, however, that in contrast to the high numbers of Armenian doctors, dentists, engineers, architects, and pharmacists the community had relatively tiny numbers of lawyers, judges and few scholars in the academia, and almost none in the diplomatic core and the public sector for which they were entitled to as of right. Indeed, it is inexplicable why a community that had an international legal cause and the right for a share in the state system did not encourage the study of law, politics and diplomacy. One may partly blame the state system that facilitated communal autarchy and pillarized identities. It reduced intercommunal bridging and integration and helped produce exclusive members of communities who had difficulty in situating themselves both in and outside the community.

The unprecedented interparty collaboration and the transnational support enabled the successful navigation of the community during the Lebanese war years with the least losses. However, migration took a heavy toll. By the early 1990s the community had diminished both in capacity, power and space.

Exhausted, consumed and weakened by the Lebanese war, the community entered phase two of its modern history, which was formulated by a number of glocal socioeconomic, technological, political and demographic factors.

The community fought back to re-shape itself and adapt to the re-formed Lebanese state system, which itself was in a process of transition. The community had to reboot its relations with the local Lebanese communities and situate within the Lebanese consociational and selectively implemented setup.

On a parallel line, the community struggled to adapt to new demographic, socioeconomic and cultural Diasporic balances and settings. Furthermore, it had to reposition itself vis-à-vis the independent state of Armenia and the Nagorno Karabagh war of self-determination. These reshuffled the nationalist agenda of the Diaspora as well as the recipients’ list of Diasporic financial allocations, which previously prioritized Beirut. And perhaps most importantly, less monolithic and more diverse than ever, the community had to take well-studied steps to redefine its character, realistically address the quests of its fourth and forthcoming generations and sustain their Armenianness.

Thanks to the continuing intra-denominational and partisan collaboration, the Armenian community of Lebanon was, to a certain extent, successful in addressing the above stated challenges up to 2005 and the decade after. However, the past five years posed new trials for the community and Lebanon in general.

Nevertheless, the legacy of this energetic community that faced several critical challenges in its one hundred years of existence is a strong indication of what it can fulfill.

Indeed, the experiences of its past decades, wise usage of new evolving factors (Republic of Armenia, a new generation of integrated identities, globalization and the digital world, etc.), designated support of the Armenian transnation and the very determination of its members, all framed in a coordinated visionary approach and concerted effort, are reassuring factors that the community will survive the current crisis and reshape itself within the framework of Lebanon, stand out on the map of the Armenian transnation, and leave its unique mark on the human spirit.

Dr. Antranig Dakessian is a professor at Lebanon's Haigazian University.