Prioritizing Homeland Healthcare

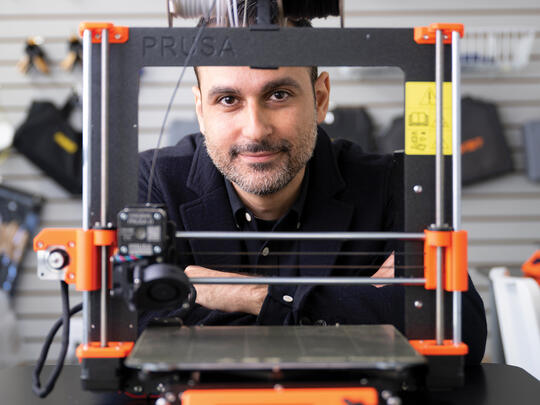

Kim Hekimian

AGBU invested in me many years ago as they did so many others. I’d like to think there’s a good “return on investment” from their support. AGBU empowers Armenians from around the world to work in Armenia and improve the situation for the country.

When Kim Hekimian began working on her PhD in Public Health, the timing couldn’t have been more opportune. Armenia had just won its independence and the soviet economy was in free fall, impacting many spheres of life including child and maternal healthcare. This collision of theory and reality prompted Kim to make Armenia as a case in point for her dissertation. The first step was conducting a national survey of infant feeding practices and researching the causes of Armenia’s rising infant mortality rates. That effort attracted the international funding she needed to launch a four-year national breastfeeding campaign to improve infant health.

Since then, Kim has taught at the American University of Armenia (AUA), working with cohorts of the Masters of Public Health program and establishing the Center for Health Services Research and Development. Today, she is an Assistant Professor at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

In our interview, Kim, an AGBU Scholarship recipient, discusses the specifics of child and maternal healthcare in Armenia and building healthcare institutions that foster change.

What first interested you about infant feeding processes and infant formula?

Throughout my studies, I seemed to gravitate to the subject of maternal and child health. I was looking for something I could research in Armenia that would be impactful. When I first visited Armenia, I considered looking at the breakdown of the cold chain for vaccine systems. Given the transition from the Soviet Union to independence, the lack of electricity, and other issues going on at the time, there was concern that vaccination coverage would be interrupted and that its effectiveness would weaken from this breakdown of what we call the cold chain.

I also knew that the systems and the technology necessary to affect that change would be out of my control. Whereas if I studied something that led to an intervention for a behavioral change, particularly a maternal behavioral change, I could follow up with an intervention. So I began focusing on how the behaviors of mothers could improve health outcomes for their babies.

What progress has been made in public health and maternal and child health since independence?

One crowning achievement in Armenia’s public health system is the decrease in infant mortality. Back in the early 90’s, a crumbling infrastructure resulted in water contamination. Because there was no electricity to boil water, women were using contaminated water in infant formula. Rates of diarrheal disease were high but, over the years, international funding helped replace all of the municipal water supply lines. Eventually, this greatly reduced the incidence of dysentery.

The Ministry of Health also made a difference. Armenia is a child-centered society, so there was funding for these priorities. I particularly credit Dr. Karine Saribekyan, a counterpart at the ministry, who was in charge of maternal child health since Armenia became independent.

What do you consider your most important contribution?

I was so fortunate for the AGBU’s support in becoming the first resident faculty member living and teaching at the American University of Armenia’s school of Public Health. In that role, I founded the Center for Health Services Research, which has continued to grow. They’ve now published over 100 peer-reviewed journal articles, which is a tremendous feat; they’re doing state-of-the-art research which has led directly to public health policy development, both in Armenia and the region.

It also gives me satisfaction to see that the graduates of the school of Public Health in Armenia are well-placed: they’re in leadership positions in the WHO, UNICEF, World Vision, you name it. Any group working on public health in Armenia is staffed by professionals who graduated from AUA’s School of Public Health.

Another source of satisfaction is that, after our work with the Ministry of Health and UNICEF Armenia, exclusive breastfeeding rose from 0% to 20% in just four years. The rate currently hovers around 35%—higher than the rate in the U.S.

What role has the AGBU played in your life?

Many years ago, I received an AGBU scholarship to support my PhD studies at Johns Hopkins University. This followed my participation in the AGBU-supported summer language institute in Yerevan, run by Dr Bardakjian. So I like to talk about the “return on investment” that resulted from AGBU support of my studies and from many of its other alumni. The AGBU does great work empowering Armenians from around the world to work towards improving the situation for the country.

What do you think the next step is for the development of Armenia’s healthcare?

In the diaspora, we have spent millions and millions of dollars on Armenia’s healthcare, but that hasn’t made much of a difference for the nation’s healthcare indicators and outcomes. Most of the improvements, including in infant health, are due to international aid efforts and Armenia’s Ministry of Health.

The diaspora has not employed the same kind of return-on-investment thinking to evaluate their programming by health outcomes. Most programs measure success by the number of clinics they renovate rather than look at patient outcomes. It’s important to help with buildings, but perhaps more important is the care that takes place inside them.

As I think about the next chapter of what I’d like to do vis-à-vis Armenia, I’d like to help Armenian NGOs working on healthcare coordinate our efforts. I’ve started setting up meetings devoted to the concept of moving from humanitarian assistance to effective institutional capacity building. We would like to develop a set of core principles around which we develop healthcare programming in Armenia.

The key question to ask is this: if your program funding stopped tomorrow, what are the elements of your program that would continue in Armenia? Moving forward, I really hope to work with people who think about how we can enable this brilliant population to improve their own health outcomes through partnerships with the diaspora.