Conversations and Connections

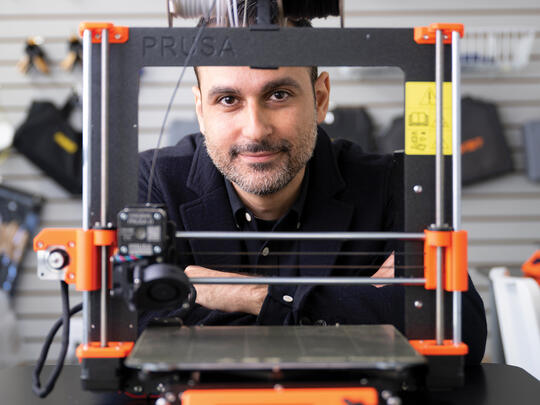

Anthony Guerbidjian

As someone who identifies as Lebanese as much as Armenian, working with Syrians has helped wear away at the negative perceptions I had of the country and its involvement during the Lebanese Civil War and Lebanon’s current political predicament. When I speak with refugees, recruit and train them, I feel like I’m building a connection with the people needing assistance and support.

Anthony Guerbidjian understands his own part in Syrian relief in an unconventional way. His academic background in international relations and his roots in Lebanon have coalesced around NaTakallam, an online language learning service that employs Syrian refugees to serve as conversation partners for students of Arabic worldwide.

Anthony, an AGBU US Graduate Fellowship recipient for his master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, worked for the United Nations before going to graduate school and co-founding an organization to help alleviate one of the consequences of the crisis in Syria.

In our conversation, Anthony takes us through the early stages of NaTakallam, discusses the positive impact it has had on Syrian refugees and language learners alike and reflects on his own affinity for Arabic.

How did NaTakallam come to be?

NaTakallam—which means we speak or we converse in Arabic—started as an idea at a brunch in January 2015 with my advisor from Columbia and two classmates who would turn into my co-founders, Aline Sara and Reza Rahnema. That month, a very heavy storm had hit the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon where a number of refugee families from Syria had been living in tents. It wasn’t the first time we had heard this kind of news, but this time we decided that something needed to be done.

Aline and I are both from Lebanon originally, but had very different experiences with language and represented two ends of the spectrum. She was a humanitarian and a journalist, born and raised in New York, and regretted not having learned Arabic at a young age, while I was born in Beirut, had Arabic as one of my native languages and taught it at Boston University as an undergrad.

We were very committed to making the idea a reality from a personal and political standpoint, so we started entering the idea in a number of competitions through Columbia and the World Bank, which helped us to build our idea into a real plan. Our question revolved around the socio-economic risks that refugee unemployment brought to Lebanon. In those first few months, we learned how to start a business from a profit and sustainability perspective and find a market gap. I have an interest in economic policy but I wasn’t someone who had started a business before. Nonetheless, we launched a pilot and saw there were a lot of people who were interested in learning Arabic online—and through refugees.

What is the draw to NaTakallam for the student?

The program is designed to be a supplement to the curriculum that a student is following in his or her Arabic class in high school or college. Since 2001, interest in learning Arabic has spiked and it has become a critical language for the US government. In business terms, this means that there is market demand for our service, especially since many times students of Arabic don’t have anyone to practice their colloquial Levantine Arabic with. For many, they choose to work with us because the social angle is very appealing. They see that the refugee problem is such a big one that governments are failing to cope with it, so it’s their manner of doing something about it in their small way.

What’s impressive is that many students are learning the language of their family. They are interested in going back to the region and talking to their family in Arabic, their ancestral language. So far we have had 800 people sign up, and we can only expect this number to grow. Eventually, we’d like to expand into an institutional client market where we engage all the major universities and government sources.

Can you tell me more about the Syrian refugees who work as teachers?

There’s a whole different story from the perspective of the refugee, who has had to flee Syria, often leaving everything behind. These are people—oftentimes trained teachers or translators—who are used to having stable jobs and being in a university, but they’ve had to cut that short and run for safety. Many have lost family members or are part of families that have been forced to scatter around the world. In Lebanon, many are restricted by their paperwork. They can’t get papers to live in Lebanon, but can’t go back to Syria, for instance, because they haven’t fulfilled their military service.

Others have had physical injuries from the war that prevent them from working in other ways. We have teachers working in Austria, Germany, Egypt, Turkey, France and Lebanon. Right now, we have a refugee who has spent six months recuperating from losing an arm. She’s one of our most dedicated conversation partners, because she has the time, wants a source of income as well as a space to express her ideas. It’s an hour where she forgets her worries and can speak to someone from a different continent who is interested in learning about her and her opinions. Psychologically, she feels very empowered and relieved.

Is there a personal component to your work with NaTakallam?

Yes, without a doubt. When I read about refugees fleeing to Turkey, I can’t help but think about the Armenians one hundred years ago. They are the same towns and cities that Armenians fled from that are hosting Syrians today. I flew from Beirut to Armenia last summer and the plane didn’t fly over Syria as it normally would, but flew over Turkey instead. This meant that we passed over Kilis and Antep, the villages where my ancestors are from, and it was very moving for me.

As someone who identifies as Lebanese as much as Armenian, working with Syrians has helped wear away the negative perceptions I had of the country and its involvement during the Lebanese Civil War and Lebanon’s current political predicament. When I speak with refugees, recruit and train them, I feel like I’m building a connection with the people needing assistance and support.

Tell me about the response you have received from the teachers?

Since our launch in July 2015, the feedback has been great. For the teachers, the program is not only a source of income, but it’s also comforting to know that they’re appreciated and able to be resourceful again. It’s very difficult to be a refugee in Lebanon, for instance, where if you’re lucky enough to be employed, you’re not going to earn a fair wage. Many also feel like they aren’t useful anymore, since they don’t have a job and their families and their country are in shambles. The program is a way for them to feel active again.

Many Syrians are impressed that foreigners want to learn Arabic—that they no longer have to learn someone else’s language. Often the case is that people in the third world want to learn the language of the first world. In our case, they are empowered by the idea that someone wants to learn their language.

As an Armenian from Beirut, how did you develop your affinity for Arabic?

Arabic is a language that Armenians find difficult. There’s a stereotype that no Armenian speaks Arabic in the proper way—we are famous for mixing the feminine and the masculine, but my mom was the exception. Whenever she spoke in public, people didn’t realize she was Armenian. She was the one who strengthened my Arabic language skills.

By high school, whenever I would write Arabic essays, my teachers would try to shame underperforming students by commenting on how an Armenian had done better than they had. While I picked up a lot from the formal, proper Arabic that my mom used to listen to on the news every night, we always spoke Armenian at home. I would get angry with her if she spoke to me in any other language. It gives me comfort when I’m in public and I speak in Armenian—it’s an exclusive circle of people who can understand.

I’ve always kept my Armenian identity as a core to my adopted identity and belonging to Lebanon. Many Lebanese Armenians go around with an Armenian flag in their car and I can relate, but I couldn’t do it myself, because it conflicts with my national identity.

It all goes back to the idea of certain NaTakallam students wanting to learn their ancestral language. Maybe there needs to be NaTakallam for Armenians? There’s no other way to be in touch with the language in a living way. Having learned Armenian and Arabic together has given me an openness for new languages and shaped me in a different way. Learning languages is just good global citizenship.

For more information on NaTakallam, please click here.

Please note that archived content may appear distorted as it has been stripped of formatting and original images.