Building for the Future

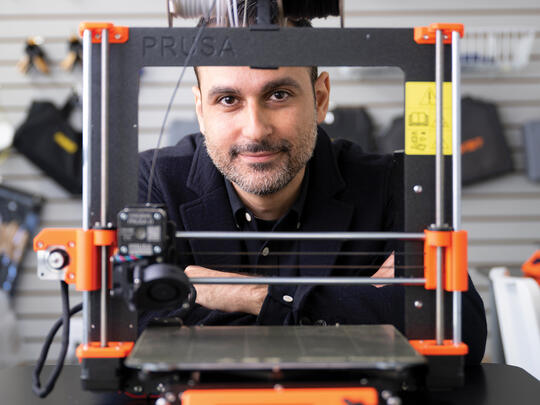

Azad Chichmanian

Like every diasporan, I came to Armenia thinking we were going to help to save someone or something, but in fact it’s the other way around. Armenia kindles all kinds of things within you as an Armenian and as a person, and you leave having been saved yourself.

Architecture has defined Azad Chichmanian’s life path since childhood, from his early devotion to drawing to his time working in construction after graduating from McGill University. His academic and professional endeavours have led him to the recent completion of the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, the largest healthcare construction project in North America and one of the largest in the world built in a single phase. Since the hospital opened in September 2017, Azad’s focus has been on Armenia; he’s now undertaking a Centre for the Performing Arts in Gyumri, a project conceived to boost the city’s economy and cultural life.

In our interview, the AGBU Alex-Manoogian School alumnus speaks about his approach to architecture, his Armenian upbringing, and the relationship between the two.

How did you first become interested in architecture?

Very early in my life, my father planted the idea in my mind without me really realizing it. I was a bit of a geek growing up – I used to love the sciences, but I also loved to draw. I’d stay up very late at night and was particularly fascinated by how animations were created. I’d study the construction lines and all the layers of work. At some point in high school, my dad said to me in passing: “You know, I can see you as an architect. It’s the balance of science and art, and you do both very well.”

He also helped me land a summer internship in an architecture office when I was still in my teens; although I didn’t realize until much later that he had paid my salary for that job himself. But by the time I went to university, I believed I’d already worked in a real architecture office. That knowledge and experience gave me a confidence boost that surely gave me a head start.

You’ve just finished building the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal. Can you tell me more about your involvement with that project?

I was the partner in charge for my firm, NEUF architect(e)s. I received a call 9 years ago from an old classmate of mine at CannonDesign about this potential new project in Montréal, so we teamed up. My role was defined as we went along, but I really did a little bit of everything, from design to operations to completion.

Construction is always very conflictual, and this project had a particularly international team. We had people from Spain, the UK, France, America, the rest of Canada, and local Québécois clients, all working under huge pressure. So cultural differences were very present. I realized to what extent Armenians are able to get along with various cultures. Where others couldn’t understand one another, I was able to be the bridge between all of these different cultures and keep the team moving in the right direction.

You’re now working on an International Centre for the Arts in Gyumri. What’s it like to be working in Armenia?

I had the privilege of contributing to two buildings here—with my own hands—in ’93 and ’94. These were difficult years; the war was ongoing, the aftermath of the earthquake, the embargo, a lack of power throughout the country and the fall of the Soviet Union. Like every diasporan, I came to Armenia thinking we were going to help to save someone or something, but in fact it’s the other way around. Armenia kindles all kinds of things within you as an Armenian and as a person, and you leave having been saved yourself.

So the Gyumri project is a dream come true. It allows me to contribute what I have learned over the years. It’s a wonderful opportunity because of the nature of the project: Performance hall, school and an experiential arts center. There is a teaching component, pure research and there will be a residency program for people from the outside to stay, teach and learn. It will also be a very public space that is constantly interacting with the city and the rest of the country.

What was your experience at the AGBU Alex-Manoogian School in Montréal?

As a very small minority culture in Montréal, we have to assimilate both into the French-Canadian context and the wider English North American context. At one point, you need to learn how your Armenian identity fits into the global context, with all these layers. Ideally, at one point, you learn that it’s just normal – there’s nothing weird or foreign about it, and that it is in fact a privilege.

The AGBU Alex-Manoogian School removed some of those complexes. The formative years in an Armenian elementary school were extremely important. You show up in a place where everybody has a long last name with a whole bunch of consonants, and amazingly they all end in -ian. Everyone has the same strange lunches their parents made. And they approach the English and French languages in a similar way. It’s like, “Okay, I speak French with a funny accent. So do you.” And slowly everybody approaches the rest of the world from a similar point of view and overcomes these obstacles together. Of course, when you’re six or seven, you don’t realize this. It’s only much later that you realize how much it helped you normalize what it means to be Armenian to be part of a diasporan culture. You realize that you bear a very precious gift and that your responsibility to share with the rest of the world.

What is your advice to young Armenians interested in pursuing a similar career?

In many ways, our upbringing as Armenians opens the door to many cultures and many fields of art, science and creativity. That very wide view is quite appropriate to architecture. There’s a cultural affinity there. It’s the process of creation— it never ends. Your design is never perfect. You have to be ready for that, as well as very long nights. But it’s a very rewarding profession: you get to make stone float, you get to make peoples’ souls soar, if you do it right. So I’d encourage anyone, especially Armenians, to enter the field.

Please note that archived content may appear distorted as it has been stripped of formatting and original images.