Armenian History, Global History

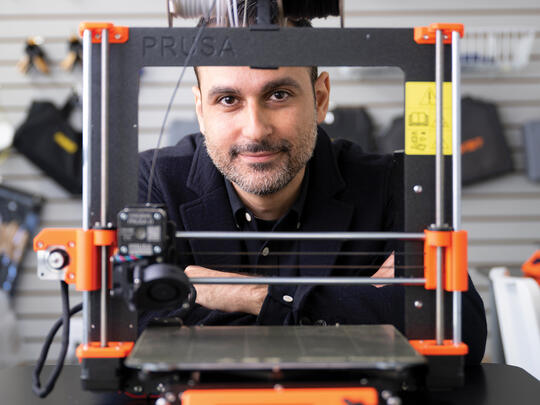

Houri Berberian

Armenians make up a very small part of the world, and to interest others in our rich and complex history, we must relate it to other peoples and histories. And that’s easy to do. The only way to relate this history is to speak of it in larger regional and global contexts.

Houri Berberian’s career has been dedicated to promoting research on Armenian history. As the Meghrouni Family Presidential Chair in Armenian Studies at the University of California, Irvine, she is using her platform to make the field more accessible, intersectional and dynamic.

Exploring the role of Armenians in revolutions around the world—particularly the Iranian, Ottoman, and Russian revolutions of the early twentieth century—Berberian uses a “connected histories” approach, allowing her to study the way different people, states and events affect each other – and contributing to a more holistic view of Armenian Studies.

In our interview, Houri, an AGBU Scholarship recipient, talks about her hopes for the future of Armenian Studies in California, the shifting ways we ought to study women in history, and how understudied historical intersections have the power to unify.

What excites you most about becoming the Meghrouni Family Presidential Chair in Armenian Studies at UCI?

Right now, I am Armenian Studies at UCI. My goal is to try to make UCI one of the key centers for Armenian Studies. I’d like to expand the endowment, add more faculty, create a minor, and much more. I would also like to extend the program in such a way that we have a robust graduate program. It’s really about an intellectual expansion, and making UC Armenian Studies a hub in Southern California. Right now, we have Armenian Studies departments at UCLA, at USC... but not in Orange County. It’s very exciting.

It’s also exciting to be one of three women chairholders, currently. I’m the only chair holder who works on women and gender issues. It’s not my primary interest, but something I have pursued in my research and publications.

What interested you in the participation of Armenians in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution?

It actually developed during my undergraduate years at UC Berkeley, when I realized that the connections and encounters between Armenians and Iranians go all the way back to antiquity. Even in that very early period, the ruling elite in Armenia and Persia, Arshakunis and Arsacids respectively, were related and our histories quite intertwined. It was fascinating to find Armenians involved in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution in the early 20th century.

To study this aspect of history was to bring Armenians and Iranians back together, so to speak, and to use Armenian-language sources in a way that had never been used when discussing the Iranian Constitutional period.

What’s the most important thing about including women in your historical and political analyses?

I think it’s critical and essential. Unfortunately, it’s only recently that scholars have become interested in studying Armenian women, much less gender and sexuality. That’s very new, and I think it’s a very welcome change. It gives us avenues through which to study Armenian history, culture, and literature that cannot be done if we focus on men only or on areas dominated by men.

Until recently, it seems the field had no interest in approaches or interpretations that diverge from the accepted national narrative or that challenge our collective perception of ourselves and our past. And gender and sexuality do exactly that—challenge. Non-feminist historians dismiss or try to divorce that kind of work from any connection to other histories. Women’s history is necessarily interwoven with men's, and knowledge of gender informs or changes our understanding of Armenian lives, culture, and history.

How does your connected-histories approach to early twentieth-century revolutions in the Russian, Iranian and Ottoman empires differ from typical approaches?

There are two conventional ways to study revolutions. The first is how area specialists do it, where the national unit, such as China, for example, is the focus. The second is comparative, which explores the similarities and differences of two units. With connected histories, we can go beyond these two approaches explore how these elements that seem separate from each other are, in reality, connected.

There’s a large revolutionary wave in the early 20th century. By focusing on the Ottoman, Russian and Iranian revolutions, I’m trying to explain how they’re connected by looking at how Armenian revolutionaries circulated through all of them. They were in all three empires and they participated in all three revolutions, so something’s going on there. That’s one way to connect revolutions – by looking at the circulation of revolutionaries, weapons, print, and ideas. The study of the circulation of all these elements provides a connected histories approach.

What advice would you give someone looking to pursue an academic career in Armenian or Middle-Eastern studies?

I recommend two things. For those who wish to study Armenians, I strongly recommend that they look at them in a global or regional context for two main reasons. First, it’s natural, just because of where Armenians are and the number of boundaries they’re crossing, not just geographical but also ideological, cultural, and otherwise. Second, because it is practical. Armenians make up a very small part of the world and to interest others in our rich and complex history, we must relate it to other peoples and histories. And that’s easy to do. The only way to relate this history is to speak of it in larger regional and global contexts.

I also recommend shoring up on one’s languages: not just Armenian but also Russian, Turkish, and French, etc. The number of graduate students who now apply with a foundation in multiple languages is both impressive and crucial. Language acquisition and a degree of fluency are extremely important because Armenian history is not just about Armenia, but the world.

Professor Berberian was recently featured in the AGBU Webtalks series. Click to watch her talk on The Changing Role of Armenian Women in New. Julfa.

Please note that archived content may appear distorted as it has been stripped of formatting and original images.