For more than half a century, Garo Nalbandian’s camera has captured the heart and soul of Jerusalem. From celebrations of faith, conflict and politics, papal and presidential visits, archeological discoveries and ancient history, Nalbandian’s catalogue of photographs is a chronicle of virtually every significant moment that has shaped the city from which he cannot part, enamored by the intersection of vibrant cultures and mystic beauty.

“I love Jerusalem,” he declares enthusiastically. “As an Armenian, Christian Jerusalem is sacred, holy land and I am proud of my community and I want to share it with the rest of the world through my pictures.”

Blessed with the energy and sense of wonder of a child, the gregarious photographer’s white hair and beard are the only traces of six decades of experience. As a photographer, his natural talent and skill with a camera have carried Nalbandian to international renown, sought after by foreign news crews including from CNN and ABC, Newsweek and National Geographic, as well as from Armenian, Greek, and Muslim religious leaders alike. His work has also been featured in television documentaries, movies, and books, while filling the racks of scenic postcards in every souvenir shop in Jerusalem.

Born in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City in 1943, the son of Armenian refugees fleeing the Genocide, Garo began his photography career at the tender age of 13, as an unpaid apprentice at the Yergatian photography studio. His responsibilities consisted mainly of cleaning the studio and running errands, but he took advantage of every opportunity to assist the in-house photographers, eagerly teaching himself how to develop film and use a camera. Eventually his boss entrusted Nalbandian to take over the residency at the studio, albeit still unpaid.

Nalbandian’s first big break came not long afterwards when a journalist from the local Palestine newspaper called the studio urgently needing a photographer to cover the arrival of U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold. Despite being just 15 years old at the time, he picked up his cameras and went to the airport to cover the visit. Hammarskjold noticed the young photographer walking backwards in front of him among the throng of reporters and cameramen and stopped to ask Nalbandian whether his pictures would be any good. Garo confidently informed the Secretary-General of the United Nations that he would see for himself on the cover of the newspaper the next day! Of the dozen or more stills he took, indeed eight would be published. “Although my boss still didn’t pay me, it didn’t matter because soon we had three times the number of calls and customers asking to do studio portraits,” he recalled. “Soon other photographers began to recognize me and asked me to work with them. I remember I was making 8 dinars which was a lot at that time. I took 1 dinar for the whole month to pay for weekly expenses, sandwiches, and the cinema and I gave seven dinars to my father.”

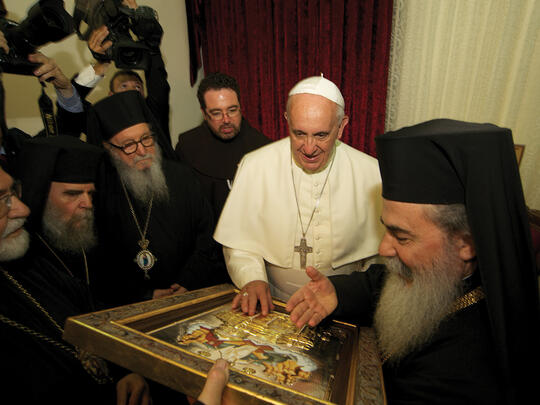

Within a few years, Nalbandian launched his own studio and became both a sought-after expert in processing and developing color film and a skilled photographer, recognized for the quality of his work. In 1961 he photographed the visit of the Russian Orthodox patriarch, publishing his pictures for the first time in Newsweek and Time magazines. Over the decades that followed, Nalbandian would be granted a privileged window on history, chronicling seminal chapters in the city’s political, cultural and, especially, religious development. As the official photographer for the Catholic Custodian of the Holy Land, which together with the Greek and Armenian Patriarchates maintain the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Nalbandian’s pictures of the historic visits of Popes Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis, have been featured around the world.

He has also served as the Official Photographer for the Armenian and Greek Patriarchates and works closely with the Islamic Wakf or religious authorities in Jerusalem as well as the department of religious antiquities in Jordan. In each case, he is widely respected not only for his artistic portraits, but also his tact and discretion. When the Muslim Brotherhood wanted to record in pictures a closed conference, Nalbandian—a Christian Armenian—was entrusted over Arab photographers. “I take my job as a photographer very seriously,” he says. “I am not there to listen and give away secrets and that is why they trust me.” In the process, Nalbandian has since amassed one of the largest individual archives of published photographs on Christian and Islamic ritual in Jerusalem—a treasure trove of historic material, some of which continue to be published in numerous books and journals around the world.