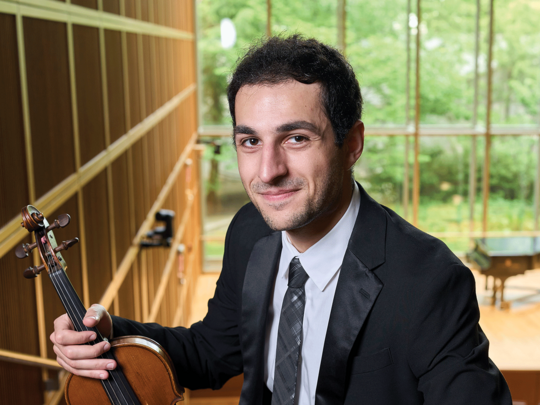

Alexis Demirdjian sat in his book-lined library commenting on the unseasonably stifling weather in The Netherlands. “No one here has air conditioning, so we’re really suffering,” he began. As a Trial Lawyer for the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Demirdjian’s life work provides a deep lens on the degrees of human suffering in the world. Perhaps that’s why he was quick to add, “Of course, everything is relative. I appreciate this rare, sun-filled day.”

When it comes to meting out justice for the gravest international crimes, there is no higher tribunal than that of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Established by a majority of the United Nations member states, the ICC’s statute states that during this century millions of men, women and children have been victims of unimaginable atrocities that deeply shock the conscience of humanity. The statute acknowledges that such crimes threaten peace, security and well-being throughout the world, with the goals of the ICC being to provide justice for victims and an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes. In doing so, the ICC seeks to raise the collective accountability and conscience of humanity.

Demirdjian, a Canadian ex-patriot, found his role in this international court after a peripatetic upbringing that saw him living in three countries by the age of ten. Born into war-torn Beirut, Alexis and his family escaped first to Morocco, and moved again to Montreal, Quebec where he was enrolled in the AGBU Alex Manoogian School, where he encountered English for the first time in his life.

“It was a shock, to hear English spoken so widely at school. We spoke Armenian and French at home. But I quickly adapted, and with this experience, my world expanded.” Demirdjian became fascinated by history and politics, and as an undergraduate at the University of Montreal, he pursued a political science degree and then a law degree. While obtaining his bar accreditation, he began to work towards a master’s degree in international law, in a separate program at the University of Quebec in Montreal.

“I first studied international relations, and then began learning more about crimes of atrocity, with the most prominent one for me being the Armenian Genocide,” he says. “I immersed myself in the details and was deeply shocked not only by the atrocities committed but by the depth of the injustice: that the victims ultimately had no day in court.”

By the end of law school Demirdjian was becoming disillusioned by the basic practice of law. “I discovered I was not interested in properties, torts, all that kind of domestic legal work. What I cared about was human rights and even more, the niche topic of international criminal law.”

He wrote his master’s thesis on the obligation of states to cooperate with international criminal tribunals, and a professor encouraged Demirdjian to look outside Canada to put his theories into practice. Demirdjian applied for roles at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague and was accepted to the team defending a general in the Bosnian Muslim Army in 2002, a high-profile case that resulted in the eventual dismissal of most of the charges.

The experience also sealed Demirdjian’s conviction that he had found his niche in international justice and criminal law. He remained in The Netherlands, moving from the defense to the prosecution office at the ICTY in 2005 where he worked on three more trials dealing with the criminal responsibility of senior civilian and military leaders. Moving to the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor in 2015, he works on teams prosecuting trials of atrocity; presenting evidence and arguing cases before trial chambers, and supporting investigation teams.

Today when one hears ‘Armenian Genocide,’ the education is still lacking. It’s a big, cloudy concept; I would like to see people talk about the detention camps by using the names of Çankiri, Deir Zor or Ayas, just as Auschwitz and Dachau are synonymous with the Holocaust.

Demirdjian’s arrival at the ICTY coincided with a time of great optimism about the reach and potential for international justice. “At the time there was a growing enthusiasm for international criminal law, particularly because we were dealing with very specific cases in Yugoslavia and Rwanda which threatened international peace and security. We had major powers backing us at both these tribunals, including all the members of the UN Security Council,” he explains. “But at the ICC, we ran into obstacles, including from the most powerful countries, such as the United States.” While today there are 123 state parties to the Rome Statute and thereby, participate in the collective ICC, some of the most powerful states are not members.

Prosecuting crimes and enforcing punishments through the ICC is a lengthy and complex process, given the size and scope of its mandate, and the very specific way crimes are defined within the Statute. Currently the Court has 14 situations open, two cases at trial and two more at the stage of confirmation of charges, ranging from Uganda and Darfur to Bangladesh/Myanmar and Palestine. The procedural steps provided by the statutory framework dictate how a case progresses from investigation to confirmation, and finally, to trial and judgement. Covering these steps raises frustrations by some states about the pace of the court’s action. The Court also relies on domestic proceedings to further the fight against impunity, as the ICC alone can only handle a certain volume of cases.

“Before a case is officially considered, the Prosecution collects statements from witnesses and documentary evidence. Once it is determined that there are reasonable grounds to believe that a crime occurred, only then it can apply for arrest warrants and issue charges or an indictment,” explains Demirdjian. “The ICC investigates crimes committed by all sides to the conflict within the prescribed limits of its jurisdiction.” Under the principle of complementarity, when deciding whether or not to proceed, the Prosecution also needs to be satisfied that genuine domestic proceedings are not already ongoing. If national authorities are meeting their primary responsibility to investigate and prosecute, the Office of the Prosecutor does not intervene and is prohibited from doing so by the Rome Statute.

In 2015 Demirdjian edited a multi-disciplinary book, The Armenian Genocide Legacy, focusing on the relevance and impact of the Armenian Genocide one hundred years later. The aim of this project was to move on from the debate as to whether the events amounted to genocide or not; the project assumed that this was now accepted and directed its focus on facts, key players, and the long-lasting impact of the genocide. Demirdjian expresses frustration at the way the word ‘genocide’ itself may limit the very actions taken to combat it.

“We get stuck sometimes on the word ‘genocide’; the discourse gets shifted from discussing what really happened, to analyzing whether or not it fits this label,” he explains. “The discussion should be more concrete: how many people have lost their homes? How many people have lost their relatives? How many churches were destroyed? Let’s talk about the real facts of the genocide. It is very easy to shift the discussion and create another forum where we’re battling simply on terms.”

He continues, “You have these international structures, and often they stop short of telling things the way they are. When the genocide in Rwanda was taking place, it took about two and a half months for the UN Security Council to use the word ‘genocide’. Although the reports were clear, there was hesitation to use the word and to take steps. Fast forward, even after the Yugoslavia tribunal and the Rwanda tribunal issued dozens of judgements, you have atrocities happening in Myanmar in 2016 and in 2017, with operations to destroy villages and kill multiple civilians but, until it’s labeled “genocide”, there is silence. Part of the problem is that the Genocide Convention is the only legal text that includes a binding obligation on states to prevent and punish genocide. Victim groups, therefore, will brandish the convention to get the attention of the international community. Hopefully, the adoption of a convention on the prohibition and prevention of crimes against humanity will relieve pressure from the Genocide Convention.”

“The French Armenian philosopher Marc Nichanian refers in his book La Perversion Historiographique (The Historiographic Perversion) to how obsession over the term ‘genocide’ can distract from the real issues. I think the term is the valid one, but I agree that the discussion sometimes derails us—let’s talk about the facts of what happened, not get hung up on a label.”

In addition to writing and practicing law at the ICC, Demirdjian is an adjunct professor at Stockton University’s Masters in Holocaust and Genocide Studies (MAHG) program, where he teaches a course on the role of international justice in the context of episodes of genocide. He also lectures on modes of liability at training programs offered by institutes in The Hague, including at the Grotius Centre of the Leiden University and the Asser Institute, at the Nuremberg Principles Academy, and recently at the City University of New York Center for International Human Rights. His focus is on sharpening perspective on the most heinous of crimes.

“Most students in the MAHG program are coming in with some basic knowledge of what genocide is and can name historical episodes of genocide. I introduce the fact that genocide is technically a legal concept that has been created by a lawyer for lawyers. Although historians, anthropologists, and sociologists study and analyze the concept—and I’m a big fan of interdisciplinary studies—when I break it down through the legal elements of the crime, students are shocked by how narrow the definition is, how difficult it is to prove genocide under law. You must demonstrate the intent to destroy a group, and if you don't have that evidence, you cannot prove it amounts to genocide. What shocks most students is that the term ‘genocide’ only protects four groups: racial, religious, national, and ethnic groups.”

For Demirdjian, President Biden’s signing of a formal acknowledgement of the Armenian Genocide on April 24, 2021 does not put the issue to rest. “We have to encourage young Armenians in the fields of art, literature, or education, to put that story out there in a powerful fashion. Human nature is such that things happen in cycles; you can see how neo-Nazism was something that we ridiculed in the 80s, yet it never disappeared, and now we see the growth of white nationalism and racial supremacy.”

“Today when one hears ‘Armenian Genocide’, the education is still lacking. It’s a big, cloudy concept; I would like to see people talk about the detention camps by using the names of Çankiri, Deir Zor or Ayas, just as Auschwitz and Dachau are synonymous with the Holocaust. I would like to see people call the victims by their names, make it tangible and complete. And that includes Turkish versions of ‘Schindlers’ who tried to protect Armenians,” he explains. “There are many nuances that are worth exploring and we can learn so much about humanity through this.”

Asked about the likelihood of achieving a world free of human rights crimes and atrocities, Demirdjian, immersed in the pursuit of such a goal, has long considered the question. “Perhaps the answer is education and encouraging that these concepts be introduced very early in schools. But how do you make that a priority and how do you make sure that this is applied around the world in an equal way? There are so many disparities in education…” his voice trails off.

Yet he concludes with deliberate optimism, “But we cannot lose hope. Yes, we still have a lot of work ahead and maybe we won’t see it in our generation, but through education we can get to the point where these ideas of ensuring safety and permanent security for everyone are a reality. That's what I hope to see for our kids and our grandchildren: that they live in a world of justice for all.”

Banner photo by Jeroen Bouman.